|

|

|

|

BUSINESS |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

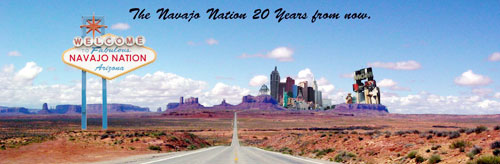

Business in the Navajo Nation

Capitalism's last

frontier

America's biggest

Indian reservation tries to stimulate private enterprise

JUST outside the south-east border of the Navajo Nation, along highway 264 in New Mexico, there is a string of shops. It is not much—a bank, a couple of fast-food outlets, a petrol station and a garage. Compared with what lies across the border, though, it feels like a boom town. Cross into the Navajo reservation and the shops abruptly disappear, to be replaced by a scruffy trailer park. As Mike Nelson, a Navajo entrepreneur, puts it: “This is the last frontier for free enterprise in America.”

When Americans talk about Indian businesses, they generally mean casinos. Since 1988, when the Supreme Court ruled that states could not ban gambling on Indian lands, a few, mostly coastal, tribes have become stupendously rich. But most big Indian reservations are in the interior, miles from potential punters. More than twice the size of Massachusetts, and with a growing population of about 200,000, the Navajo Nation is the biggest of the lot—and the most in need of private enterprise.

There are only about 400 businesses in the Navajo Nation. With a few exceptions, such as a coal mine, they are tiny. The official unemployment rate is about 50%, and the median income is less than half the American average. What little money is generated in the reservation tends to leak out. Three times a month—when the welfare cheques arrive, and when government workers are paid—Navajos stream out of the reservation to stock up on groceries, car parts and alcohol in border towns. The local joke goes that the tribe's biggest export is dollars.

The reservation has produced plenty of entrepreneurs. Navajo silversmiths and weavers are justly famous. But the tribe's division of economic development lists more Navajo-run outfits off the reservation than on it. One of these is the garage on highway 264. Its owner, Donald Dodge, did not want to leave the Navajo Nation. He did so because he could not afford to wait years to obtain a business licence.

Anybody who wants to set up shop in the reservation must conduct an archaeological survey, obtain a letter of support from the tribe's president and jump through up to a dozen other hoops. These regulations, put in place to protect Indians from white traders, now bind native entrepreneurs large and small. Timothy Halwood recently obtained a permit to take small groups of tourists into the Canyon de Chelly. The process took two years.

Another problem is land. Like other reservations, most of the Navajo Nation is held in trust by the federal government. Because Navajos do not own their land, they cannot use it as collateral to finance a business. To make matters worse, almost 8,000 people claim grazing rights over land that often extends into towns. These rights have no paper value and so cannot normally be sold to developers. The result is a paradox: a vast, underpopulated area where it is hard to find a commercial site.

A third problem is politics. The Navajo Nation has an 88-member legislature and 110 local chapters. “It's a lot of chiefs,” says Joe Shirley, the Navajo president. This is a big reason the Navajos have been slow to get into the casino business. Plans to do so were approved in 2001, but feuds over how to divide the spoils between tribal and local governments led to delays. The Navajos' first casino is expected to open this autumn, some 150 miles from the nearest big city, in a market that has been saturated by smaller, nimbler tribes.

The dysfunctional politics of the Navajo Nation does have one good effect: it forces the tribe to concentrate on private enterprise. In other reservations almost all businesses are run by the tribe, either directly or through a corporation. Although such firms can be profitable, they are as susceptible to political meddling as any nationalised industry is (see article).

Under Mr Shirley, the first president to serve two consecutive terms since the 1970s, the Navajo government is steadily hacking away at the red tape. In 2006 it took control of business-site leases from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As a result, it now takes a year or two to obtain a lease—down from as many as five years in the 1990s. Alan Begay, who is in charge of economic development, reckons it will eventually be possible to grant a business lease in about a month.

Some of the Navajo Nation's local governments are going further. Since 2002 the town of Kayenta, near Monument Valley, has levied a 5% sales tax and spent much of the proceeds on housing and infrastructure. The town has a land-use plan and a long-term strategy for attracting businesses. All of which would be taken for granted outside Indian country, although it seems radical here. But nothing happens very fast in Navajo country. Ask a bureaucrat how he intends to remove one of the many obstacles to business, and the first answer is usually “slowly”.

Navajo Nation

The roads joyfully

travelled

Driving as lifestyle,

roads as cafés

I GET up early to catch a Navajo businessman as he opens his tyre shop before heading off to see someone at Albuquerque Studios, an upstart film outfit. Then it is back home to Los Angeles. I retrieve my car, merge into the northbound traffic on Sepulveda Boulevard, and relax.

What sitting in a café is to Paris, driving is to Los Angeles. It may not always be pleasurable (those Parisian waiters can be a pain, too) but it is the city’s essential experience. Yet a growing number of Angelenos seek to deny this fact. Some hole up in “walkable” neighbourhoods and boast about their use of the skeletal subway system as though they lived in a temperate version of New York. They should do what I did when I first moved to Los Angeles, and read a book written almost four decades ago by a middle-aged British architecture critic.

|

|

|

|

| Asphalt spaghetti |

Reyner Banham’s “Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies” is by a large margin the best book ever written about LA. Yet few Angelenos have heard of it, and some of those who have read the book affect a disdain for it. Mike Davis, a much more fashionable and gloomy writer, nodded at Banham’s work in the title of his book “Ecology of Fear”, which tries, and fails, to up-end Banham’s vision of the city.

“The Architecture of Four Ecologies” opens with a handful of conventional verdicts on the city, one of them delivered by my predecessor in my first job at The Economist (“Personally I reckon L.A. as the noisiest, the smelliest, the most uncomfortable, and most uncivilised major city in the United States.”) The rest of the book does not so much rebut such criticisms as discard them. To appreciate Los Angeles, Banham explained, you will have to forget about comparisons with other cities and think again about the meaning of the word “civilised”.

The bits from Banham’s book that I remember, and occasionally quote to bemused friends, have nothing to do with architecture in the conventional sense. There is Banham’s wide-eyed description of the intersection of the 10 and 405 freeways as “one of the greater works of Man”. There is his devastating and still-true dismissal of downtown, which despite enormous amounts of effort and urban-renewal money continues to convey “a strong feeling that this is where the action cannot possibly be.”

Banham understood a fundamental fact about Los Angeles: it is not a city of places but a city of movement. He learned to drive just before moving to the city, and immediately understood the special function of roads there. LA’s freeways are not simply a means of getting from A to B, as in other places. They are what marketing people call a lifestyle—“a special way of being alive”. Or, if you like, a civilisation. On them, Banham noted, Angelenos often spend the most relaxing and rewarding hours of their day.

Near the end of his book, Banham concedes that Los Angeles is not entirely perfect. It was true then (the book was published just six years after the devastating Watts riots, when smog still choked the city) and it is true now. For one thing, the traffic is worse. The city’s seemingly relentless expansion, which Banham recognised as a source of its energy, turned out not to be relentless after all. Preservationists and urban planners have made the city less ugly but also less interesting.

Still, the Los Angeles that Banham describes endures. Last summer I went to see “Transformers”, a delightfully daft film set mostly in California and Nevada. It took me half an hour to realise that the scene of the final battle was downtown Los Angeles. But I instantly recognised the 210 freeway.

YOU do not have to drive very far on Interstate 40, which runs along the southern edge of the Navajo Nation, before you see advertisements for casinos. All promise groaning buffet tables and “loose slots”. One of the most frequent advertisements on KTNN 660AM, the “Voice of the Navajo Nation”, is for the Apache Gold casino. This is rather galling.

The Navajo Nation does not yet have a casino. In the 1990s a powerful alliance of cultural traditionalists and evangelical Christians stymied efforts to build one. Now the tribal government wants to build six. That will take a long time, if it happens at all, and there is no guarantee that the casinos will succeed. But it is easy to see why they want to try.

|

|

|

|

|

| Revenue stream |

The Indian gambling boom began in 1987, when the US Supreme Court ruled that the government of California had no right to regulate bingo and card-game operations on reservations. Within ten years Indians across the country had built casinos bigger than any in Las Vegas or Atlantic City. These days they have combined revenues of about $8 billion. Not since vast herds of buffalo roamed the Great Plains has it seemed so easy to make a killing.

Outside of East Coast behemoths like Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun (property of the Mashantucket Pequots and the Mohegan tribe), Indian casinos tend to be short on glamour. Compared to casinos in Las Vegas, most have little marble, relatively few card tables and a severe shortage of cocktail waitresses. A casino built by one of the Navajos’ neighbours is little more than a large tent. But Indian casinos have a lot of slot machines, and if they are in the right place they make a lot of money.

The main body of the Navajo Nation is not in the right place. It is hundreds of miles from the nearest big city, and other tribes have beaten the Navajos to prime locations near Albuquerque and Flagstaff. Unless the tribal government can work out revenue-sharing deals with outlying Navajo communities that are better placed, its casinos are likely to amount to little more than a tourist sideline and yet another potential addiction for its own people.

And the Navajos are late to the party. Last year I spent a delightful day talking to members of the Morongo band of Mission Indians, who run a slick casino-hotel near Los Angeles. In the mid-1980s the tribe was on the verge of collapse. Now tribal members are buying up pottery, re-learning their traditional language and even resurrecting old ceremonies (which they discovered in anthropology books). They are also pouring money into new enterprises, just in case the casino business goes bad.

Indian casinos exist because of what psychologists call cognitive dissonance and everyone else knows as hypocrisy. Americans wish to gamble. Yet they cannot bring themselves to liberalise gambling, which is, after all, a sin. So it is necessary to allow a few exceptions to the general rule. These include Nevada, riverboats (which are often little more than casinos surrounded by moats) and Indian tribes.

Can this peculiar state of affairs possibly last? Since the Indian-casino boom Michigan and Iowa have liberalised their rules on gambling, and more states will surely follow. After all, it makes no sense to outlaw an activity that could be heavily taxed while permitting the same activity in places where it can be taxed only lightly. Thanks to the downturn in the housing market, state accounts are filled with red ink. They are likely to look at the gleaming casino-hotels, and wonder how they can get hold of such riches. Even hypocrisy has its price.

JUST before dinner I go out for a drive. Three or four miles east of Chinle I round a corner and there it is: an Ansel Adams scene.

No artist has shaped views of the American West more profoundly than Adams. He was a photographer and an environmentalist of the old-fashioned, save-the-trees kind; he died in 1984. His ghost still lingers. It is impossible to visit Wyoming’s Grand Tetons, California’s Yosemite National Park or the Navajo Nation without recalling his images. For most sightseers, Adams’s ghost is a benign presence (“Gee, that looks just like the calendar on my kitchen wall!”). For serious photographers, it is a mocking reminder of their own inadequacies.

The excellent “Ansel Adams: 400 Photographs”, released last year, contains several superb pictures of Navajo country. The most famous is an image of White House, an Anasazi ruin wedged into a cleft in a giant, bulging cliff. It is simple and perfect.

|

|

|

|

|

| Ansel's West |

Adams conveys the mass of the cliff and the subtle cross-hatching of sedimentary layers and “desert varnish”—vertical stripes made by minerals leaching out of the rock. He includes a corner of sky, for context. If you have seen it, you can forget about taking a picture of the same scene that will satisfy you.

Adams was not only an artist; he was also drawn to the technical side of photography. He fretted over the mechanics of exposure and printing, writing several impenetrable books on the subjects. But he could improvise, too. One of his most famous pictures, the eerie “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico”, was taken in a hurry, without a light meter. Rushing to capture an extraordinary light, Adams somehow recalled that the moon has a luminosity of 250 candles per square foot, and quickly exposed a plate. He was spot on: the black areas in his photograph are utterly black, the greys and whites glowing.

Adams used a large-format camera, an unwieldy machine now used only by fancy wedding photographers and Adams impersonators. But he didn’t have to. In 1937 he was given a 35mm camera, then a novelty, and asked to test it.

He took it to the Canyon de Chelly with Orville Cox, a cattle-wrangler and the great painter Georgia O’Keeffe, and snapped a few shots. The result is a masterpiece: O’Keeffe, wrapped in black, casts a sly, pixieish glance at Cox, who is silhouetted against a cloudy sky. She is almost imperceptibly out of focus, a reminder that even the master made mistakes.

Adams was a propagandist on behalf of nature, particularly California’s Sierra Nevada range. He perhaps succeeded too well. An odd thing about his pictures (though it does not seem so odd these days, since so many others have copied him) is that few of his landscape images contain people or their detritus. A photograph of Monument Valley, in the northeast corner of the Navajo Nation, carefully uses a rock to obscure a road.

Adams photographed people too, but, unless they were fellow-artists, they often seemed unhappy: an influential series of pictures captured the Japanese interned in California during the second world war. His work suggests that people and nature cannot coexist. That view, unfortunately, is still held by many in the West.

Then there is his influence on other photographers. When Adams made his most famous images, photography was not generally considered art. Now it is, rather ponderously so. His dramatic style has become a cliché, frequently verging on bombast when emulated by less talented people. And his technical know-how has encouraged others to believe that measurement is a substitute for artistic vision. Some photographers inspired by Adams, such as Phil Kember, a Californian, are producing good work. A great many others (like your correspondent) are not.

ONE of the painful things about being a journalist is that you often have to listen to people’s accounts of their experiences with other journalists. Few of these stories are complimentary, and some are so dismal that they seem to demand an apology on behalf of the profession. So I feel slightly apprehensive when Edward Richards, a retired saw-mill operator, abruptly launches into a tale about a visit from a French TV crew.

All was going well, apparently, until the subject of identity came up. The French interviewer asked Mr Richards whether he was Navajo and then, just as he began to say yes, added “…before you are American?”

|

|

|

|

|

| War heroes |

Thankfully, I will not have to apologise this time. Mr Richards found the experience highly amusing. The question of whether it is possible to be loyal both to the nation and to a racial or ethnic group is acute in France. It is rather less acute in America, with its many hyphenated identities (African-American, Armenian-American etc), and for Navajos it is almost comical. Indeed, perhaps no group manages its double identity so breezily.

Above public buildings, United States and Navajo flags fly side-by-side. When speaking to each other, Navajos may switch from their native language into English and back several times in a single sentence. The local radio station plays a mixture of traditional chants and the Dixie Chicks. Navajos are enormously proud of their contribution to America’s military adventures, and continue to leave plastic flowers at the war memorial in Window Rock. But their proudest moment was essentially Navajo.

During the second world war, hundreds of Navajos were dropped behind Japanese lines and told to report on fortifications and troop movements. It was an extremely dangerous task, and would have been fruitless if their messages had been intercepted. So they developed a code based on Navajo objects and translated words. In his book “Diné”, Peter Iverson explains how the code worked. A submarine was beeshlóó’—iron fish. The letter A was wólachíí (ant); B was shash (bear).

The Japanese seem to have realised that the code was based on the Navajo language, but were unable to break it. So successful was the experiment that the American military kept the code under wraps until the late 1960s—which meant there were no parades or public thanks. These days the “code talkers” are proudly remembered in Navajoland. Their story allows Navajos to celebrate both their own culture and America. After all, the code only worked because Navajos are bilingual.

What the Navajos are not is “Indian”. Despite the legacy of the radical American Indian Movement and new websites like Indianz.com, few have much use for the term. The president rebukes me when I use it, and others glaze over at my attempts to compare their experiences with those of other tribes. This is not political correctness. Navajos are even less likely to describe themselves as “Native American”—a term used almost exclusively by bien pensant whites. They are simply Navajo, or Diné (“people”).

Just because Navajos are exceptionally good at negotiating between cultural worlds does not mean they do not make mistakes. A few weeks ago the Navajo Times carried a story about a move to create a Diné medal of honour for those who have served in the armed forces. The speaker of the Navajo legislature apparently thought this would be a good idea. Navajo veterans did not. Explaining that only Congress can award military medals, they crushed the plan by a vote of 34-0. Three of the intended recipients responded that they would rather have a sheep.

THE first sign that I am entering Navajo territory appears just north of the Gallup, in New Mexico. Men line the side of the road with their right hands stretched out. The more enterprising wave dollar bills. They have left the Navajo Nation to work, and are now trying to get back in. As much as anything I am told in the next few days, they reveal the crisis facing the Navajos.

Nowhere in America—not the Mississippi delta, not the Appalachians—is poverty so widespread as in the Navajo Nation. In 2000, when the last census was taken, fully 43% of residents lived below the poverty line. Perhaps 80,000 out of 200,000 people lack running water, which explains the large plastic containers in the backs of many trucks. Even in the towns, residential streets are often impassable in an ordinary car.

|

|

|

|

|

| American yard |

Pull off the road almost anywhere in the Navajo Nation, and the ground glistens with broken glass. Despite the ban on alcohol, drink is a big problem here. So is obesity. The traditional Navajo diet of mutton stew and fry-bread is not exactly wholesome, although it is better than the stuff served up in the fast-food outlets.

Most reservations used to look like the Navajo Nation. Then came the boom in Indian gambling, which hugely enriched tribes lucky enough to be located near big cities. By any conventional measure, formerly obscure groups such as the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians and the Mashantucket Pequots have far overtaken the Navajos. Increasingly, they define the image of Indians in America. But measuring success in Indian country is not a simple matter.

“We still have our language, our colour, our stories and our medicine people”, Joe Shirley, president of the Navajo Nation, tells me. “We’re not getting ahead of ourselves.” When he goes to other reservations, he is struck by the fact that many people do not look Indian. At least, he says, Navajos have not forgotten who they are.

This is true. Mr Shirley could have added that the Navajo Nation is blessed with abundant natural resources. Oil and coal—nobody knows quite how much—lie beneath the ground. There is uranium, too, although mining it is politically unpalatable. The Navajo Nation contains three of the most starkly beautiful places in America: Antelope Canyon, Monument Valley and the Canyon de Chelly.

The reservation produces the astonishing Navajo Times, a sober publication that ranks with the best provincial newspapers anywhere. It also has legions of silversmiths and weavers whose work is sought by many Americans, and would conquer a wider market were anybody to come up with a half-decent marketing plan.

Then there are the Navajos themselves. They are delightful and amusing company, but for a journalist their appeal goes beyond this. Apart from Northern Ireland, I have never been to a place where people are so competent at explaining their problems to outsiders. This stems from the cultural self-confidence that Mr Shirley talks about. Feeling secure in their own identity, Navajos can look at themselves clearly.

Most of all, the population of the Navajo Nation is growing. Which makes it all the more urgent to do something about that wretched economy.

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2008 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. All rights

reserved. |

|

|