![]()

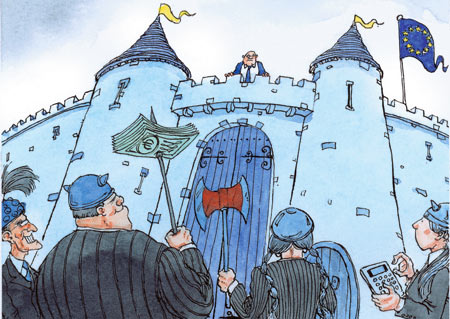

Corporate debt

Barbarians at the

gates of Europe

|

|

|

|

|

Leveraged buy-outs are

growing in Europe, and so are doubtful debts

INEOS is not yet a household name. The British bulk-chemicals producer was formed only eight years ago and the New Forest, its base in southern England, is better known for ponies than for petrochemicals. But when INEOS tapped the debt markets last month to finance a €9 billion ($10.8 billion) takeover of some of BP's chemical assets, it found no shortage of interest. According to one person who worked on what proved to be one of Europe's largest-ever leveraged deals, creditors had within weeks offered €25 billion, almost three times what INEOS needed.

The size, speed and success of INEOS's debt-raising gives a sense of the sea-change taking place in Europe's capital markets. It was evident in the ballroom at London's Four Seasons Hotel on January 11th, when hundreds of hedge-fund executives and other fund managers heard how they could lend to INEOS, one of the world's biggest chemicals companies. A few years ago, that type of credit institution barely existed in Europe, where lending was a clubby affair handled mostly by banks. But the funds have emerged in search of the yields that lending in highly leveraged transactions can command. In INEOS's case, 490 of them expressed an interest in lending.

The sea-change is also reflected in the fancy array of debt instruments that INEOS coaxed from creditors. They were a far cry from the “plain vanilla” syndicated loans it would have expected in an earlier credit cycle. They included three tranches of term loans, some mezzanine-like debt called “second lien”, and ten-year junk bonds, denominated both in euros and in dollars. All were rated below investment grade, meaning they carry a high risk of default. But each segment was of a record size for Europe, says Malcolm Stewart of Merrill Lynch, an investment bank that co-ordinated the transaction. For once, most of the demand came from creditors in the euro area, rather than Americans. “The European leverage market has clearly matured. It is no longer the little sister of America,” says Mr Stewart.

Such maturity suggests

that if—and it is a big if—credit conditions remain benign, there are pots of

money to be lent to the right borrower. This has sent bankers on a quest for

deals even larger than INEOS's. Several believe that

within the coming weeks or months there will be a leveraged buy-out in Europe to

rival—at least in nominal terms—that of America's RJR

Nabisco, the grandfather of them all. It was sold for $25 billion to a buy-out

group in 1988, and its story was told in a bestselling book, “Barbarians at the

Gate”.

Large corporations are also potential beneficiaries. They could either gear up for acquisitions, or they could raise debt defensively, as Britain's BAA, the world's largest airport operator, may do to fend off a highly leveraged potential bid from Ferrovial, a Spanish conglomerate.

This makes sense as long as interest rates or a downturn do not put borrowers under intolerable strain. Already, some lenders are beginning to worry that they may be in too deep. Data from J.P. Morgan imply that debt taken on in the sub-investment-grade market in Europe to finance a typical leveraged buy-out rose to nearly eight times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation in 2005, up from just over seven times in 2004.

|

|

|

|

|

According to Standard & Poor's LCD, a leveraged-finance unit of the ratings agency, the volume of such leveraged loans almost doubled last year, to €123 billion, growing at a much faster rate than in America, where there are also signs of strain. Meanwhile, although default rates are low, S&P has detected an increase in the speed with which new European borrowers breached their loan covenants last year, forcing them to negotiate expensive waivers with their creditors.

An area of particular concern to the ratings agencies is the extra debt that borrowers are piling on to their balance sheets. This is either because their private-equity owners want dividends (as at Debenhams, a British department-store chain that found its leveraged loan issue last year was unpopular among institutional investors), or because the company has been “recycled” from another private-equity group. Gala, a British bingo and casino operator, stood out last year for its ability to borrow money repeatedly to pay off its private-equity backers, and to finance the £2.2 billion ($3.8 billion) acquisition of a rival, Coral Eurobet.

The rating agencies say that the deteriorating credit quality of those trying to finance adventurous takeovers could spell trouble. They expect an increase in default rates this year or next, even if the economic conditions for borrowers do not deteriorate much. Bankers are keen not to be left holding a toxic tranche of unsellable debt if the credit cycle turns. “There is a universal consciousness that it is a very aggressive market,” says Richard Howell, a managing director at Lehman Brothers, an investment bank. “People are aware there is a lot of risk in the system.”

The repercussions of a fall in credit quality would be felt far beyond the leveraged-loan market. The corollary of the enhanced liquidity provided to borrowers by hedge funds and other institutions is that they too are highly geared. It is easy to imagine their own lenders getting cold feet if credit conditions turn.

Yet one man's

misfortune is another's opportunity. Banks and hedge funds are increasing their

expertise in the distressed-debt market, where the most pungent credits will

eventually end up. Not all of them will be able to benefit if the leveraged-loan

market contracts. But the vultures are out there already sharpening their talons

for the day when that happens.

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2006 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. All rights

reserved. |