Tuesday October 21st 2003

Financial accounting 1: session 2 first part

In the first session we laid the ground to feel the need for accounting in running a firm. We described what is a firm, what is its goal, what is the job of a manager. I described a first example encompassing many of the concepts of accounting. And we finished with a part explaining what is money, and how did it historically develop. Now in this session 2 we shall enter into the nuts and bolts of accounting.

When we run a firm we need to keep track of all sorts of information, some of it of a monetary nature. The accounting system keeps track, in an organized manner, of this information of a monetary nature. We shall look at the first entries into the journal and see how they're treated by the accounting system. The accounting system classifies (puts in order) the information about the daily operations of the firm, contained in the journal.

The journal contains the word "jour". And "jour" means "day".

The journal records the "elementary operations" of the firm on a daily basis.

In a small firm, on a given day, you can have 10,20, or 50 elementary operations or more. The elementary operations recorded in the journal are called "transactions".

The information about the transactions will be classified into what we call "accounts". It is just an organization process, nothing more, of the raw information of a monetary nature contained in the journal. Because the result of accounting is the production of organized and useful information we sometimes say that accounting produces a dashboard of the firm.

An organization process is something we do all the time. For example when we received e-mails instead of keeping all of them into the "incoming box", we dispatch them into various folders we created: "school", "family", "housing", "mary", "other_friends", "jokes", "technology", "summer_job", "chess_club", etc. Organizers are also tools to classify in a useful manner many things we plan to do: appointments, errands, other objectives, books to read etc. Accounting is nothing more than that.

We all do accounting in our checkbook.

Most checkbooks have a little booklet in front to keep a record of the checks that we write. It usually looks like this :

| Previous Balance 250 |

||||

| Number | Date | Description | Euros | Balance |

| 107 | Oct 10 | School club fees for the semester | 50 | 200 |

| 108 | Oct 12 | Electricity for august and september | 23 | 177 |

| Oct 14 | Money from Grand'Ma (for the coming Christmas) | + 60 | 237 | |

| 109 | Oct 15 | Scarf for Mary | 25 | 212 |

As we can see we can also record money coming in our bank account with this booklet (money from Grand'Ma). It is not precisely designed for that, but why not ?

In our bank account we rarely go down to zero. We could. We could even go to a negative balance, it all depends what agreement we have with our banker. When we go negative, we have to pay agios to the bank.

This is called single entry accounting : for each movement we make a single entry that describes it and records the value of the check or of the money coming in (and, for convenience, we compute and note the resulting balance of our bank account).

Accounting was done this way, and only this way, since about 3000 bc until sometime after 1000 ad.

In fact the first writings, that appeared about 3000 B.C. in the Sumer civilization (with the cuneiform scriptures), in the Middle East, were accounting records. They recorded the number of cows owned by some rich people, or the quantity of wheat purchased by the king etc. The other early writings were law codes and epics. Geographically Sumer was located exactly where is today Southern Iraq.

Cuneiform writings

Geographic location of Sumer

Early civilizations

(from

https://www.hyperhistory.com/online_n2/maptext_n2/maptext.html)

Since, following Herodotus, we define the beginning of History as the date of the first writings, we can say that Accounting is exactly as old as History. And this makes sense because writings were invented to keep a durable record of important facts in society. These important facts were what we owned, what we exchanged, the rules to live together, and the story of our people.

The limitations of single entry accounting :

Merchants coming from all over Europe to the Champagne fairs of the XIIth and XIIIth centuries felt the need for more sophisticated accounting than just single entry accounting.

source : https://www.historylink101.com/middle_ages_europe/middle_ages_maps.htm |

Champagne fairs

|

To understand their problem let's look again at our checkbook :

Suppose that on Oct 16 we do for 80 of work for Joe. Now Joe owes us 80 but he will pay us in say only 15 days. What entry to make in our checkbook ?

We can refine the example: our balance on the 16th is 212. Suppose we need to pay 250 on October 20th. What to do ? We may write the check number 110 and ask the recipient not to cash it until we receive Joe's payment.

| Previous Balance 250 |

||||

| Number | Date | Description | Euros | Balance |

| 107 | Oct 10 | School club fees for the semester | 50 | 200 |

| 108 | Oct 12 | Electricity for august and september | 23 | 177 |

| Oct 14 | Money from Grand'Ma (for the coming Christmas) | + 60 | 237 | |

| 109 | Oct 15 | Scarf for Mary | 25 | 212 |

| Oct 16 | Work for Joe (80) to be paid to us at the end of the month | - | 212 | |

| 110 | Oct 20 | Rent for the months of august and september (250), but we asked the landlord not to cash the check until the end of the month... | 250 | ? |

What we see is that if we want to keep track of our "financial position", taking into account money that will come in and money that will go out, our single entry checkbook is not longer sufficient. We have to make all sorts of notes around the main column "Euros", and the balance of our checking account is only one piece of information among a more complicated set of figures we want to keep track of.

The same problems complicated the single entry accouting system of merchants. So they invented a more efficient accouting system, called double-entry accounting. And it proved so efficient, that it is still used today not much modified from 800 years ago ! We shall see that it is a system that solves very nicely the problem of money owed to us but to be received later, as well as payments that we will have to make in the near future for things already received.

Double-entry accounting will also play many more wonders: it will produce a complete and very useful "dash board" of the firm, in monetary terms. At any point in time we will know "how we are doing", and we shall be able to appreciate "how we performed" over any period of time.

Back to our checkbook : instead of covering the booklet of our checkbook with notes about money due and money to be receiced in the future on the pages where we keep track of the checks and cash balance, we shall make these notes on other pages not from the cash booklet.

The creation of accounts :

The checkbook booklet will be limited to recording movements on our bank account. Other monetary information will be noted elsewhere. The piece of paper on which we will keep track of work done for Joe and what he already paid and what he has not paid yet will be called "Joe's account". And we shall see in a minute how we technically keep this account.

Said another way : when the money movement does not take place at the same time as the corresponding operation (for example, doing some work for someone, purchasing a product, or a service that we shall actually pay later, etc.) we need to make recordings elsewhere than in our checkbook booklet.

Remember : keeping an accounting system is nothing more than classifying monetary information, a bit like we classify our incoming e-mails in various specific folders instead of keeping them all in one single "incoming mail" folder.

Double-entry accounting

Double-entry accounting I will sometime call "modern accounting". It was invented over a period of time between the XIth and the XIIIth century in Europe. And the first book explaining clearly the procedures was written by Luca Pacioli ( 1450-1514).

The Mathematician Fra Luca Pacioli, 1495 painted by Jacopo de Barbari, |

Luca Pacioli's famous friend |

Going into the nuts and bolts of double-entry accounting :

We start from the journal, as always. All the monetary information to pilot a firm is contained in the journal. The only problem with the journal is that it is too big, it is not organized, it is not synthetic. It is not convenient to see very quickly "how we're doing", and take the appropriate decisions.

Example of the journal entries at the beginning of a firm (a firm founded by Joe) :

In order to really understand what's going on some, some preliminary comments must be made.

First all Joe decided to found a firm. It will be important to distinguish Joe and his firm, called Joe's firm. Joe's firm is different from Joe, the person. And Joe will have two rτles: he is the owner of the firm, and in this little example he is also an employee of the firm.

Secondly the business Joe decides to enter consists in purchasing goods and selling them to clients without any transformation in between. For example Joe's firm is a clothing shop: it purchases cloths and sells them. It is not like the Chinese snake manufacturer that sold toys, but purchased wood and tape and glue. The clothing shop purchases its goods from a dress manufacturer.

| Clothing shop | |

| Goods purchased | Goods sold |

|

|

| Manufacturer of dresses | |

| Raw materials purchased, and equipment | Goods sold |

|

|

It is simpler to begin the study of accounting with the study of shops that purchase and sell goods with no intermediate transformation. Shops do have a "value added" too but not as concrete that of manufacturers.

Typically the clothing shop will buy dresses 50 apiece and sell them 100 apiece. It looks like a wonderful business, where we don't have much to do. But we shall see in this course that it is not quite that simple. It is possible to earn a good living running a shop, but it is also easy to lose money.

Comment number 3: once Joe has put £5000 into the cash box of his firm this money now belongs to the firm, no longer to Joe directly. (The firm itself belongs to Joe, OK.) There are rules about what a firm can do with its money and what it cannot do. These rules are different from what Joe can do with his own personal money.

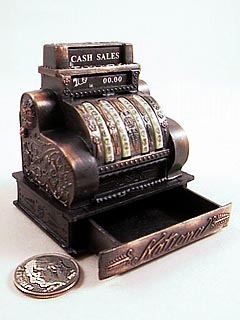

We shall distinguish the two places where the firm keeps its money: the cash box (also called the till, or the cash register), and the bank. We shall keep a separate account for each.

If you stand for a while in front of a shop you may see the manager of the shop stepping discreetly out of his shop, with a folder under his arm, and going to the bank nearby. In his folder he has cash, that he is taking to the bank in order not to have too much cash on his premises.

Once again : do not mix up Joe and his firm.

An anecdote illustrating the importance of distinguishing the firm from its owner :

I once had a business in publishing and I was renting from

a landlord who also had a publishing house, "Les Editions Entente", in the same

building on the floor beneath my office. He wanted to sell his business, and

thought of me. He asked me whether I was interested in buying "Les Editions

Entente". I said: "Why not? Can I see the accounting documents?" He gave them to

me. They showed a turnover of 2 million French francs, and a profit of 300 000

French francs. A pretty good performance! I look more closely at the accounts

but couldn't see the rent. I asked: "Your firm doesn't pay rent?

- No, the building belongs to me.

- Well but there should be a rent. In fact the figure

would be about 300 000 French francs. In truth your profit is 0."

He looked at me with eyes looking like plates. To try and

make him understand that he was making a gift of 300 000 French francs per year

to his firm, which explained the profit, I asked him: "If I purchase the firm

from you will there still be no rent?

- Oh no, in that case you will owe me 300 000 French

francs per year."

He was mixing up the accounts of his firm and his own personal accounts. He thought that he was selling a highly profitable firm (therefore worth a lot of money) when he was actually selling an unprofitable firm. A firm making no profit usually is worth about nothing. Someone could argue: "but it can pay you a salary!" Yes but you don't need to purchase the whole firm in order to sell your work. In fact this is an interesting question in the economics of work markets, that we shall not address in this course.

When we say that Joe puts 5000 pounds into his firm it means that afterwards Joe has 5000 pounds less of his personal money, and his firm owns 5000 pounds. And from now on what we are interested in is what the firm does with its money. We are no longer interested in Joe's personal money. If later on we sometimes say "Joe purchases a van", it is an erroneous and misleading way of speaking : it is Joe's firm that purchases a van.

In these simple businesses the owner usually is also employed by the firm, so the boss may receive a salary for his work. In our example Joe will receive a salary of £1000 paid at the end of each month. This salary is paid to Joe because he works in this firm. You don't pay salaries to shareholders, you pay salaries to workers in the firm, that is to people who sell their work to the firm.

Let's begin the accounting treatment of the journal entries :

I will describe what is done nowadays. I will not try to explain step by step how it developped historically over a couple centuries in the late Middle ages. So for a little while we shall get a bit technical and then retrospectively the logic will be crystal clear, but not necessarily at first.

The first entry of the journal is "On January 1st 2003, Joe started his business with £5000 in cash. He puts them into a cash box." We reorganize it into two accounts :

1a. In a first account, called the capital account, we record the founding money and who it comes from. The account looks like this (all accounts have exactly the same structure, I want all of you to keep to this exact lay-out in this course) :

| Capital account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 1.1.2003 | Initial capital coming from Joe paid in cash. |

5000 |

|

The entry is made on the credit side. Joe becomes someone who gave something to the firm and is recorded as such. The capital account is the piece of paper on which we record who the founding money came from, and only that information. What the firm will do with this money is another matter. It is not recorded here.

1b. In a second account (remember: an account is just a piece of paper on which we note things) we record that the firm receives some cash. This second account is called the cash account :

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 1.1.2003 | Initial capital coming from Joe paid in cash. |

5000 |

|

Every operation described in the journal (they are called "transactions") gives rise to two entries in two different accounts, and one is in the credit column and the other one in the debit column. It is this mechanism - which at the moment we just learn to apply - which was designed by merchants 800 years ago, and turned out to be very powerful in recording what happens to the firm.

So in the Cash account, we record £5000 in the debit column. We shall see in a minute why it is logical that it be recorded on the debit side.

Remember to always draw your accounts cleanly and properly. Accountants are very tidy, to the point of being nit-picking, it is necessary to keep correct accounts when there is plenty of information to classify. Anecdote : the etymology of the Sergent Major pen. Listen to the sound file (≈ time 59 minutes of sound file 2a)

Let's turn now to the recording of the second transaction into two accounts.

The second transaction is "January 3rd, he takes £3000, out of the cash box, to put them on a bank account".

2a. First of all we record a movement in the cash account. It had £5000 after transaction 1. Now £3000 will leave the cash account.

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

1.1.2003 3.1.2003 |

Initial capital

coming from Joe paid in cash. Money taken from the cash account to be put in the bank account |

5000 |

|

The £3000 that leave the cash account are now recorded on the credit side, that is the other side from recordings of money coming in. This is logical: this way we readily see that what remains in the account is £2000.

For the description accountants also have rules. But in this course ("Accounting for non accounting students") I will accept any description that describes well the transaction.

2b. And, every transaction giving rise to two entries into two different accounts, we now have to make a record of what happened to these £3000 that left the cash account. They arrive into the bank account. So (always our concern to keep track of information, and classify it) we take a new sheet of paper, call it the "bank account" and make a recording in it.

| Bank account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 3.1.2003 | Money taken from the cash account and put into the bank account |

3000 |

|

Once again here the value (belonging to the firm) arriving into the bank account, it is "debited".

Rule : The information of every transaction recorded in the journal will be reorganized into two accounts (one on the debit side, and the other one on the credit side). That is why this modern accounting technique is called "double-entry accounting". This rule has no exception.

Remember : a transaction is an elementary operation involving the firm where money or value changes hands or places. Examples of transactions :

In all these examples, that we shall study at great length, some money or some value changes hands or places.

Examples of operations which are not transactions :

Treatment of the third transaction

The "treatment" of a transaction consisting in classifying the information into two accounts is called "posting".

The third transaction record in the journal is : "January 3rd, he (that is his firm) purchases a van, £2000 paid by check".

In this transaction value (a van) will enter the firm, and money (by check) will leave the firm.

3a. For recording the money leaving the firm by check we already have the account : the bank account. So we make the new entry shown below :

| Bank account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

3.1.2003 3.1.2003 |

Money arriving in

the bank account coming from the cash box Money leaving the bank account to pay for the van |

3000 |

|

Note that in the descriptions above only the part in bold is useful

information. For the first line, we already know that it is money coming in the

bank account because it is on the debit side. And for the second line, we

already know that it is money leaving the bank account because it is on the

credit side. So the standard (and rather terse) descriptions are :

for the

first line : cash

for the

second line : van

3b. For the second half of the double entry posting the purchase of a van we need a new account: an account where we record purchases of transportation equipment. Let's call it the "transporation equipment account"

| Transportation equipment account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 3.1.2003 | Purchase of a van paid by check |

2000 |

|

Transaction number 4 : " January 7th, the firm buys some goods, £1000 paid in cash"

Like for any transaction this describes a movement of value: goods come in the firm, and cash leaves the firm.

4a. Let's start with the transaction half for which we already have an account: cash leaving the firm

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

1.1.2003 3.1.2003 7.1.2003 |

Initial capital

coming from Joe paid in cash. Money taken from the cash account to be put in the bank account Cash leaving the firm to pay for goods |

5000 |

|

We shall study later the three, and only three, methods for the firm to pay for something, we have already met two methods:

pay with cash

pay by check

and, a method we haven't yet met, give a promise to pay later (called an "I.O.U")

Here we pay for the goods with cash (the simplest way) so the recording is very simple: the cash account is credited £1000

Note, by the way, that it was possible to pay £1000 with cash, but it would not have been possible to pay say £2500, because the cash account cannot have less than zero money in it, just like my pocket can have money or can be empty, but cannot have less than zero money in it.

This remark does not apply to the bank account. With proper agreements with our banker, we can "have less than zero money" in our bank account. More on this later.

4b. Goods enter the firm. We don't yet have an account for goods in the firm, so we open a new account, and record that the firm receives goods. We could call this account "Purchases of goods account" but the custom is to call it "Purchases account".

| Purchases (of goods) account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 7.1.2003 | Goods (for resale) entering the firm (paid with cash) |

1000 |

|

In a shop the "goods" is the name given to products purchased for resale. Dresses are goods in a cloth shop, tables are not.

We could be tempted to record the goods purchased into a large account called "things purchased" where we would also record the van, office equipment and every else purchased. This would not mess up the arithmetic of accounting, but it would definitely mess up the usefulness of the information we are creating. This is just like the process of classifying our e-mails : if we have too big a category "other e-mails" it is as useless as having no folder classifying system at all for our incoming e-mails. That is why we do not record purchases of goods in the same account as acquisitions of equipement (and we distinguish in different accounts the different types of equipment).

Transaction number 5 : "the 9th, the firm sells some goods, for £1500, received in cash"

The most important transactions in a firm : sales !

Here the transaction is : goods leave the firm as sales, and money (in the form of cash) enters the firm. Let's start with the part of the posing for which we already have an account

5a. £1500 of cash enter the firm

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

1.1.2003 3.1.2003 7.1.2003 9.1.2003 |

Initial capital

coming from Joe paid in cash. Money taken from the cash account to be put in the bank account Cash leaving the firm to pay for goods Cash from sales |

5000 |

|

Note that this transaction does not specify how much of the goods present in the firm where sold in this selling transaction : presumably about £750 worth of goods (at purchasing price for the firm), but it is not recorded here.

Traditional shops dislike to tell clients their purchasing price. And they dislike even more to tell their clients who is their supplier (although usually it is not very hard to figure out). But note that suppliers who accept to sell directly to final customers irritate their distribution network. They end up loosing it, and then they have to enter the business of distributing themselves their products to final clients. They discover that it is a different activity from selling to shops. It is called "downward integration".

5b. Sales. We need to open a new account : the "Sales account"

Because of the rule of double entry accounting, "in every double entry recording one account is debited and another one is credited", the sales account is gonna be credited (because the cash account was debited)

| Sales account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 9.1.2003 | Sales of goods paid in cash |

1500 |

|

it is always a bit difficult at first, when learning accounting, to accept that "a sale is a credit". We shall discover little by little the deep logic for this. But it is too early to study the deep logic now. So the best for the time being is to carve it on stone in our mind : a sale is a credit.

Sixth transaction : "On the 31st, the firm pays a salary of £1000 to Joe."

Like every transaction, this transaction records a movement of money or value : money leaves the firm in exchange for one month for work consumed by the firm.

Cash or check ? Good question. The recording in the journal is flawed : it should have specified cash or check. Let's go to the payroll office and ask them : the tell us it was paid by check. OK. So we shall credit the bank account, and debit a new account "salary account"

6a. Credit the bank account for paying Joe at the end of the month

| Bank account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

3.1.2003 3.1.2003 31.1.2003 |

Money arriving in

the bank account coming from the cash box Money leaving the bank account to pay for the van Money leaving the bank account to pay Joe salary |

3000 |

|

6b. Open a new account recording salary payments

| Salary account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 31.1.2003 | Joe salary for the month of January (paid by check) |

1000 |

|

Break time