Finance with a review of accounting

Introduction, double-entry accounting

Go to a newer more detailed version of lessons 1 to 4

Nature and scope of the course

This is the first lesson of a one semester, 39 hour course entitled

"Corporate Finance". The name "Corporate Finance" has been used in so many

different contexts (physical investments, financial investments - short term, or

long term -, structure of liabilities, financial analysis, portfolio theory,

etc.) that it has somehow lost a precise meaning. The course I'll teach could be named "The firm in its financial and economic environment". We will spend a

couple lectures reviewing accounting techniques to measure value, and then shift

to more specifically financial questions and techniques.

Problem of value. Real value, promises and money

In economics the problem of value (value of goods, value of services, value

of assets, physical, financial, etc.) is a central problem. When - say, we

are a European firm - we ship cars to a client overseas, how to get paid? With

what? Goods, money (what currency?), promises? How to be sure what we shall get paid with has the "proper value" we expect? China, as of the end of 2017, holds about $1200 billion worth of promises from the United States (see major foreign holders of US Treasury securities.)

Recording values

Accounting has a way of recording values in transactions. We will review it.

Accounting is not concerned with the variation of the present value, for us, of an asset,

depending upon the time at which we will actually become the owner of it in the future. If

Carrefour gives us, today, a 45-day-draft promising to pay us 20 000 € in a month

and a half, we record it as having today the value 20 000 €.

Difference between Finance and Accounting

This is not so in Finance. We will see what is, from a financial point of

view, the present value (the value today - the price at which we could possibly

sell this "financial security" to somebody else today) of Carrefour's promise.

Tangible things with different values to different people

The same thing may have different values to different people. This is the reason why, when it bought Skype, eBay paid $2.6 billion for the purchase of the firm from Skype's founders, while to some other compagnies Skype would have been worth no more than a few million dollars at best. Generally speaking, a purchase of tangible things (as opposed to financial securities) is always an "arm-wrestling contest" between the seller and the buyer, the buyer trying to figure out what's the value of the thing to the seller, and the seller trying to figure what's the value of the thing to the buyer. Then a price in between is reached. Skype's founders were smart enough to sell their firm for a price close to its maximum value for eBay, which was way higher than the value to themselves. Notice that any seller in a flea market does the same when he appraises his potential client to figure out how much he should be willing to pay for some object. Think for instance of some book completing the buyer's collection. We shall see that, as regards financial securities, life is simpler, and (in the standard theory, called MFT, for "Modern Financial Theory") each product has the same value to everyone.

Creating value

A central problem of Finance is this: I have some value in my pocket

today, how to transform it into more value in the future? (Surprisingly enough,

we shall see that finance addresses too, and answers the question: how to

transform it into more value now.) Obviously if I have

100 000 € in my pocket today, and I do nothing with it, it will not grow. I have

to do something with it to produce more value. There are two basic ways to

proceed.

Production

The first way is this: acquire machinery, hire people, purchase raw

materials, transform these raw materials plus the labor of your workers into

products, and sell them. If you did things intelligently (taking into

consideration demand, markets, competitors, etc.) you will make a profit, in

other words your initial value will grow. The standard way to describe this

profit is to say that it is the remuneration of your organisational work, and of

the risk you accepted to take.

Speculation

The second way to proceed is to astutely use the variation of value of

certain assets over time (if you can control this variation it is all the

better). Here is a real life illustration of this second way. Right after WWII, the

father of an acquaintance of mine purchased, for a very low price, all the

bank notes that the US authorities had prepared for France but that De Gaulle

refused to use, calling them monkey money. Then he sold these bank notes, little by little, over several

decades. And his son inherited a great estate from his father speculation.

Speculation doesn't always deserve its bad name. It is bad when an economic agent "corners" a market (like silver, or grain) to make the price skyrocket, and then sells slowly his assets, making a huge benefit, and disregarding the problems he creates. But speculation is at the heart of finance: how to preserve value?, how to acquire things that will protect one's savings?, what are the urban development prospects of this area of the city?, etc.

A modern firm is an organization of people, with production equipment, located in some premises, financed by shareholders of the capital, to produce goods or services and sell them on markets. It is the basic element of capitalism.

Industrial firms are recent. Industrial revolution. The current revolution

Industrial firms are relatively recent in History. They arose only after the

beginning of the industrial revolution, in the second half of the XVIIIth

century in England and on the Continent, when new sources of energy (the steam

engine of Newcomen (1663-1729), later improved by Watt (1736-1819) made it

economically rational to have large factories with many workers located in the

same place. In the centuries before those times, "industrial" production was

achieved mostly by the putting out system: merchants organized the production

of goods, for instance textiles, in the dwellings of many people, who each had a

loom in their home. (Of course, there is no clear cut date for the evolution,

and one could mention the "manufactures" launched by Colbert in XVIIth century

France, according to the mercantilist way of thinking. These factories, however,

were not financed and did not function following modern capitalist techniques.)

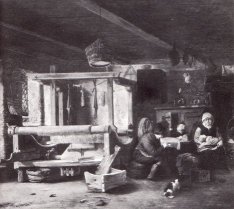

The loom in the home of a weaver.

Source: Fernand Braudel, Civilisation matérielle, économie et

capitalisme, XVe-XVIIIe siècle, Vol. II, Armand Colin, 1979.

And in the Middle Ages, industrial production essentially did not exist. Most of the population was rural (more than 90%) and produced goods for auto-consumption. Some craftsmen worked in cities. Society as a whole was not based on free markets, free production and free exchange.

Furthermore, the only "physical products" built with a manufacturing process (as opposed to agricultural products) were stones for buildings, bridges and walls, pieces of wood for various constructions, and some metallic objects like hoes, nails, and later on the first clocks. None of those required plants for their production. Big ships were built in shipyards controlled by the prince.

In other words, industrial firms gathering in the same location large amounts of production equipment and large numbers of workers are recent. The laws structuring legally these firms mostly date from the XVIIIth and XIXth centuries (corporations, limited liability, etc.).

We live in a world that changes very fast, and we take it for granted, but it has not always been like this. Until the Industrial Revolution men traveled at no more than 20 to 40 miles per day, since the beginning of times. You were born during the course of the computer revolution - more precisely around the time of the first microcomputers. These machines profoundly changed the banking and financial world, financial exchanges, even the role of money. And it is likely that these changes will go on, and that means of payments will undergo further tremendous evolutions.

Commercial firms are older

The story of commercial firms is somewhat different. Modern commercial firms

can be traced back to the merchants of northern Italian city-states which arose

in the XIIth century, when they took their independence from the Holy Roman Empire.

This was also the time of the advent of peace in Western Europe, after all the

barbarians invasions, the last one being the Normans'. (The Turks and the

Mongols came later, but they stopped before Vienna.) And peace used to lead to

economic activity, to commerce and to prosperity. Hence the demographic growth,

the cathedrals, the big projects like the crusades (of such lasting and

nefarious consequences), etc.

Venetian and Genoese merchants

Venetian and Genoese merchants traded between the Orient and Western Europe.

Large trade fairs developed all over Europe. Some famous ones took place in

Champagne, in Lyons, in England (Scarborough fair...), in Germany, in northern

Italy (Plaisance). A fair in Spain, at Medina del Campo, dealt only with

securities and money (bills of exchange, coins - no merchandises). In the XIIth

century, Italian merchants began to devise a system of accounting more

sophisticated than just keeping track of how much money is in the till. This was

the beginning of double-entry accounting, that was almost full-fledged by the

end of the XVth century (first accounting manual by the Venetian monk and

mathematician Luca Pacioli, 1494).

The Mathematician Fra Luca Pacioli, 1495

painted by Jacopo de Barbari.

Modern banking

Modern banking activity appeared around the same time. (Note that Christians

were forbidden by their church from receiving an interest on the money they lent;

they could only lend money with no interest. This is one of the reasons why Jews

often turned to banking. They were expelled from England in 1290, from France in

the early XVth century, and from Spain in 1492, but in fact each time they were

invited back - except in Spain -, under stringent conditions, because they

provided useful services.)

Climax of the Middle Ages

The XIIIth century is the climax

of the civilization of the Middle Ages, before the calamitous XIVth century

(Plague, Hundred Years war between England and France, rebellion against the

Yuan Mongol rule in China, etc.) and the reconstruction and reorganization of

the XVth century (civil wars in France, Spain, England, consolidation of states,

great discoveries, etc.) opening onto the Renaissance. Yet the XIVth century is

also the century of the greatest abstract ideas, contributed by the Nominalists

(Ockham (1285-1349), Oresme (1320-1382)...), arguably more powerful than the ideas of the Renaissance.

Founding capital

The first modern commercial firms with a founding capital, split between

stockholders, are the English East India Company, 1600, and the Dutch East India

Company, 1602. The first modern bank, with a capitalistic structure, is

the Bank of England, incorporated on July 27, 1694, as a private joint-stock

association, with a capital of £1.2 million. It lended right away its entire

funds to the government of William and Mary. In return for the loan of its

capital to the government, at 8%, it received the right to issue notes and a

monopoly on corporate banking in England.

Modern financial ideas are very recent (and they don't

work well)

Since we shall mostly study large industrial firms (their investments, the securities they sell,

the money they borrow), our topic is no more than two to three centuries old.

In fact, we shall see that modern financial ideas (proposing a model of interaction

between money, value, time, risk and return) date from no earlier than the

middle of last century (Markowitz, 1952, Sharpe 1965, Black & Scholes 1973, etc.). In the first half of the XXth century,

finance people began to "discount" future cash flows, but without a fully

developed theory (Fisher 1930, Keynes 1936, Williams 1938). In 1900, Louis

Bachelier had introduced the idea of random walk in the movements of security

prices, but the power of his ideas was not recognized until the middle of the

century. And before the XXth century, finance people took their decisions

according to their hunch. On the other hand, "modern financial theory" developed

between 1950 and 1980, has proved rather weak to explain and predict security

price movements, and more generally the world financial situation (Asian Crisis

of 1997, High-Tech values bubble of 2000, "the irrational exuberance of markets",

as

described by Alan Greenspan, etc.). People like Warren Buffett say very politely

that MFT (modern financial theory) is a bunch of mathematical techniques that

are as useless as they are sophisticated. And when Buffett expresses such an

opinion, we pay attention because he became the richest man on earth

using other investment techniques (based on the so-called Graham Dodd ideas, in

truth a bunch of rather intuitive and commonsense ideas, but applied carefully, in detail, and rigorously). So our study will be down to earth. We will

learn sturdy tools, which have proved their usefulness, to measure value and to

evaluate investments - keeping in mind that the field is still open to news

ideas.

The need to monitor value creation

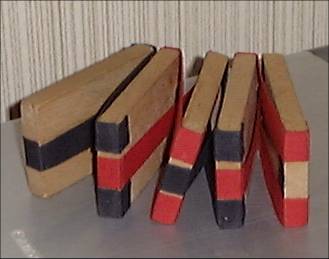

To get a feel for the operations of a firm, and all the information that is produced and that we must monitor in some organized way, let us look at the beginnings of a small manufacturer of wooden toys. In this example, the firm will manufacture funny toys called Chinese snakes.

A Chinese snake.

Selling to wholesalers, retailers or the public

It is a real example, just a bit simplified. I found this toy in France at a small handicraft

producer in Burgundy, a guy who had decided to live in the countryside and earn

his living making wooden toys that he sold mostly to wholesalers

and retailers and, occasionally, to

visitors to his small workshop like myself. The choice of which market we shall try and sell

to is an important one. Running a firm selling to wholesalers is different from

running a firm selling to retailers, or to end consumers. The job of the salespeople is not

the same. The costs are not the same. The gross margins are not the same either.

Detailed description of 18 steps

Let us imagine and note all the important events from the outset until the

end of the first four months of the Chinese snake mfr. (Mfr stands for "manufacturer", and "Mfg" stands for "manufacturing".)

1) First we need to gather some money, because we shall have plenty of expenses to set up the firm and to launch the production and the selling organisation, before we earn our first euro from sales. We want to start with, say, 50 000 €. Usually we will not be able to get this initial money from a bank. So, first of all, we gather 50 000 € from our own savings (10 000 €), from our family, it is called "love money", (20 000 €), and from friends (20 000 €), either as a loan, or as participation of partners.

2) Secondly we open a bank account and put the 50 000 € on the new bank account. We could, of course, put the money into our own personal bank account we already have, but it would be a bad idea because we would soon mix up personal expenditures from expenditures for the firm. And, anyway, it is legally mandatory.

3) We need premises. We rent a place and pay right away six months of rent, 5000 €.

4) Let us take care of "human resources": we hire two people to work with us. One will be in charge of manufacturing, and one will be in charge of selling. You, as the boss, will be in charge of the administrative chores, relationships with the authorities, with the bank (you will be the one "having the signature" for the checks), and you will organize the work of the other two people. Each employee, including yourself, will cost 2000 € per month. One of the persons has to be in charge of purchasing. Suppose this is you the boss that will take charge of that too.

5) We need to purchase office equipment: a table, a file cabinet, and a desktop computer. This, plus some expenditures for fixtures, amounts to 3000 €.

6) We are at the end of week one. We purchase a used van, 4000 €.

7) We purchase a mechanical saw, 2000 €.

8) We purchase raw materials, wood planks, tape and glue, 2000 €. Let's keep track of how much money we have spent so far: at the end of the second week, we spent 16 000 €. We still have 34 000 € in the bank account of the firm.

9) The manufacturing employee begins to make toys. The salesperson sets up a selling program, and begins to call potential clients (they are called "prospects").

10) At the end of month one, we have to pay salaries, and the charges that go with them (social security, etc.), 6 000 €, the telephone line (we also got a telephone) 1000 €, and we also spent 1000 € in gasoline and hotel expenditures. So we are down to 26 000 € at the bank.

11) At the end of the second month, we have to pay the same expenditures plus, say, electricity and maintenance expenses in the workshop: altogether 10 000 €. We are down to 16 000 € at the bank.

12) We also note that we have wood wastes of 20 percent: that is 80 percent of the wood we purchase ends up in our toys and 20 percent are wastes or rejects.

13) We also note that the manufacturing employee produces 50 toys per day, about 1000 toys per month. And the salesperson visits on average two prospects per day in France.

14) At the end of month 3, a great news: our first sale. Carrefour orders from us 2000 toys. The final price of these toys will be 20 € per toy, on Carrefour's shelves. But we sell to Carrefour at the price of 10 € per toy: a first sale of 20 000 €! We celebrate in a restaurant, 100 €.

15) Carrefour will pay us in 45 days. In the meantime we have a "bill" signed by one of Carrefour's chief purchasers (a piece of paper called an IOU; more technically, it is called a 45 day draft - in French, "une traite" or more generally "un effet de commerce") certifying that we shall get paid in a month and a half.

16) At the end of month 3, we have to pay the usual salaries, 6000 €, and various other expenditures 2900 € (of course we have a detailed list of these expenses). We ship the 2000 toys to Carrefour. They no longer belong to us.

A first "recap"

Here is an important point. If we list what the firm has at the end of month 3 we get

this: 7000 € in the bank, a piece of paper from Carrefour promising a payment

of 20 000 € in a month and a half, no raw materials left,1000 toys ready for

sale, a used van, a mechanical saw, and some office equipment.

We could also say that we have other things in this firm: we have a know-how, we have operations which run (we can produce objects and generate sales), we begin to have a reputation, a good name, and so forth. But none of this is taken into account in accounting procedures. A firm is more than a collection of elements, it is a "machine" that works and - when it's well tuned - that creates value. Somebody else may buy this firm way more than the sum of the values listed above - even if it has no relationship with his other activities, that is even if it is a "standalone" acquisition. (We shall see that if the firm has connections with his other activities the story is yet another one.)

Note that we did not compute any value for the stock of finished goods. It is less, hopefully, for us than the 10 € per toy at which we sell them. You may remember from your accounting course the techniques to evaluate stocks (LIFO, FIFO, etc. on the various elements to manufacture the toys).

17) We purchase raw materials: 1000 €. At the end of month 4 we pay the salaries (but the boss decides not to pay his own salary - well it is not really a choice:-) is it?): 4000 €. And we pay various expenditures 1500 €. At the bank we are down to 500 €. We shall wait until Carrefour's check to purchase more raw materials, and to pay with a delay the boss salary.

18) We receive the check from Carrefour: 20 000 €.

And life goes on, because the firm is a "going concern".

Points illustrated by the toy manufacturer logbook

There are plenty of things to be learnt from this simple example.

The 18 steps listed above form a logbook, that is, a list, on a daily basis, chronologically, of what happens in the firm. It is full of information, some of it of a monetary nature, some of it of a non-monetary nature (for instance, productivity measurements).

A great many pieces of information to monitor

So, first teaching: we have to keep track of all sorts of pieces of information to run a firm. A central one of course is the amount of money, at any point in time, left in the bank (plus the cash in the till). But we also have information about raw materials, about assets, about clients, about productivity of employees (that one is not of a monetary nature), about expenditures, like gasoline, or hotel expenditures, etc. All this information has to be monitored. It is the job of the manager.

What is accounting

Accounting is a set of techniques to organize and present in a useful manner the monetary information recorded in the logbook. The information, properly organized and presented, in a synthetic way, is very useful to managers. (All the relevant information is already contained in the logbook, but it is not displayed in a synthetic and useful form.)

The journal

In accounting, the part of the logbook that records very precisely all the monetary information, on a daily basis, concerning the monetary operations of the firm is called the journal. The sale of 2000 toys to Carrefour for 20 000 € is a monetary information, and must be recorded in the journal, even though no money is exchanged on the day of the sale. But value is exchanged. The IOU from Carrefour is not money, but it is close to it, and at any rate it is value.

Promises issued by firms and promises issued by countries

On a much larger scale, you know that the United States, for the past few years (revised in 2013), import every day of the order of $2 billion worth of goods more than they export. They do not pay the difference with $2 billion of additional money, that would be added to the dollars already in circulation in the world, they pay mostly with short term treasury bills (promises by the US government to pay the money soon, and these promises - unlike the IOU of Carrefour - bear interest). Dollars may be shipped out temporarily to foreign suppliers, but they soon come back to the US to purchase TBills (because the US government budget is in chronic deficit and the government borrows to complete its budget, and it gets its dollars from foreigners holding them from surplus trade) and other securities issued by western agents (hedge funds and others), so it is equivalent to the US paying for its surplus imports with TBills. This is why we talk, concerning the US financial situation about the "twin deficits" (the trade deficit, and the budget deficit), which feed each other. Dollars are only a vehicle for payment, they are not the final reserve of value kept by foreigners. Here is the list of US treasury securities holders in late 2008 (see local file if link no longer works). The short term interest rates paid by the US government on its TBills have been raised gradually, over the three years 2003 to 2006, from 1% to more than 5%, in order to keep the US TBills attractive. In late 2008, however, due to the consequences of the subprime crisis, the Fed was forced to lower the rates to almost zero. These decisions are taken by the Federal Reserve of the US, and its president. For 18 years, it was Alan Greenspan. Before Greenspan, it was Paul Volker, the new economic advisor to Obama. Since 2006, it is Bern Bernanke.

The imbalance between the Orient and the West is an old story

The problem of the imbalance of trade between the Orient and the Western world is not exactly new: since Antiquity China has had, most of the time, a positive balance of trade with West (exporting more silk, china and spices than it imported western goods), the balance was paid with precious metals (silver and gold)*. The new aspect is that now the balance is paid with promises (mostly US government bonds). The amount of the US foreign debt is so big that it is seriously threatening the stability of the world monetary system. There is a serious risk of a collapse of purchasing power of the US dollar either with respect to other currencies (exchange rate collapse) or with respect to american goods (domestic inflation).

* It even lead to the regrettable Opium wars with England in the middle of the XIXth century.

How to preserve value?

The problem of how to preserve value is a big problem in economics. A $100 dollar bill, that I keep in my pocket, is not a very good way to

preserve value. First of all, it doesn't grow. Secondly, when I got it 4 years

ago, it purchased about 125 €, whereas now it purchases only about 80 €. Also,

two years ago, it bought 4 barrels of petrol, and today only one and half. Would it be better for me to keep gold? Or sheep? If I were to go and live

on a desert island for a while, would I prefer to take with me dollars, euros,

gold, securities, machinery, or sheep (and rice)?

The Norwegians pump oil from the bottom of the North Sea and sell it in exchange for financial promises of various sorts (in order "to preserve their wealth"). Is it a smart way to proceed? What's the best way to protect the value of their oil assets? Do the Norwegians have many options?

The Gold Standard era

During the times of the Gold Standard, roughly 1870 until WWI, all important

currencies in the world were convertible into gold at fixed rates, by anyone who

held such currencies. An ounce of gold was worth $20,67, a pound sterling was

worth $4,86, the French franc ("le franc germinal") was worth a certain amount

of gold, etc. After WWI, even though a tremendous inflation had occurred during

the war, most countries tried to go back to the Gold Standard, at the previous

exchange rates. This was done by England in 1925 - by Churchill, then chancellor of the exchequer - and proved to be a catastrophic decision for

the economy of England. They pulled out of this fixed rate in 1931. The French

devalued the "franc germinal" by 80% in 1928. The US set a new relationship

between gold and the dollar in 1934: from then on you needed $35 to buy 1 oz.

of gold.

The end of the Bretton Woods Gold exchange standard era

(1944-1971)

The US guaranteed their dollars with gold up until 1971. If you

were a foreign central bank holding dollars, you could always change your

dollars for gold at the US Treasury, with this exchange rate 1 oz. of gold = $35

(a Troy ounce is about 31 grammes, a cube of gold a little more than one centimeter

side). In August 1971, President Nixon cancelled the

convertibility of dollars into gold, because the US gold reserves were low, and

the amounts of dollars held by foreigners, in comparison, were too high. This sent

the world into a new monetary system of floating exchange rates, with no

metallic standard any more. Due to various economic causes in the 70's, the price

of gold reached $850 for one ounce on January 21, 1980. Then, it declined, for the next twenty five years,

to a zone between $300 and $500. In September 2005,

it is at $445/oz., and slowly rising.

What's so special about gold?

Essentially nothing. The precious character attributed to gold is somewhat artificial.

It dates at least from the times of Croesus, a king of Lydia, in the first half

of the sixth century b.c. who decided to mint coins made of gold. Lydia, in

western Asia Minor (nowadays, Turkey), had sources of alluvial gold. (Remember

also the Pactole river of Phrygia, conquered by Lydia.) Once again, if you go

live on a desert island, you don't take gold with you, you take food and some tools.

Today's topic is not money, nor reserve of value, but an introduction to accounting for cash and for value. I would like us, however, to think, at leisure, about these questions that we will encounter again and again.

The little example introduced the main accounting

concepts

The little example of the foundation and beginning of operations of the toy

manufacturer already touches upon many of the questions treated in accouting and in finance:

- founding capital

- 50 000 € in our example

- relations with banks

- investments

- roughly speaking, investments are "expenditures for things that will be in use for several years in the firm"

- to pay a salary is not an investment; to buy raw materials is usually not an investment, because we will use them up very quickly

- whereas to buy a van is an investment (except if we are in the business of buying and selling vans...); to buy a computer is an investement ; to buy office equipment is an investment, etc.

- all those are "physical investments". We shall see, and study, more important physical investements, like building a whole plant, or buying a whole firm.

- and we shall also study "financial investements".

- assets

- simply speaking, the assets are "the things the firm owns"

- we made a list of those in our example

- it was the very beginning of the asset side of a balance sheet

- relations with clients, client paper

- Carrefour gave us "client paper"

- it has value, even though it is not money

- it belongs to the assets of the firm

- it was one of the breakthroughs of Italian merchants to realise that they should count this as value, but elsewhere than in the cash account, to distinguish the nature of the value.

- purchases

- the word "purchases" is usually used for expenditures on things bought to be resold (with a margin)

- more generally, "charges" is used for the expenditures on things that will be used quickly (like fuel; if not already, like work of employees) to produce goods.

- stocks

- we like our stocks to "turn" quickly

- but even if they stay for a long while, we don't call them investments

- bank account

- the money "we have at the bank"

- "current" expenditures

- another name for the "charges", that is the expenditures for things consumed quickly in our operations (purchases, salaries, telephone, rent, travel expenditures, fuel, etc.)

- "capital" expenditures

- another name for the "investments" (van, saw, computer, etc.)

- employees

- etc.

The little example is close to reality

The example is a simple one, but it is rather realistic. The steps

listed correspond reasonably well to what you have to do to start a small wooden

toy manufacturing firm. (The only thing unrealistic is that it will take more time and much more efforts before you sell to Carrefour, but we may very

well get clients within three or four month. In late 1992, I founded my third

firm, a firm producing language learning methods on CD-ROMs, and I got my first

sale to FNAC in July 1993. FNAC paid within one week, provided you granted them a further 3% discount, which I

accepted cheerfully ...)

Do not run out of cash. What is bankruptcy

Fundamental principle is: do not run out

of cash (either in your till or in your bank account; the two elements are part

of what is called "the quantity of money, M1, in society"). Because if you go very low on cash and put yourself in a situation

where you will not be able to pay a forthcoming expense, then you will go

bankrupt. For a few months, the bank will not allow you to go "negative", that is

to become a debtor in its books. It will impose that your firm stay a

creditor of the bank (in common words "has money at the bank"). And therefore in

the books of your firm, the bank account will be in debit. (We shall see this in

more detail in a little while.)

Why not pay with IOUs?

Question: if we run out of cash, why not pay some suppliers with

IOU's? After all, we accepted an IOU from Carrefour. Why is the situation not

symmetrical?

Answer: The situation is not symmetrical because we are a new firm with no credentials, whereas Carrefour is a well established and well known firm and "Carrefour's paper is solid". When we have build trust, we will be able to pay with IOU's, but right now the machine supplier would probably not accept an IOU from us. (See discussion below.)

Note that the same question applies to the United States buying goods from the Rest of the World. But it's a vast question pertaining to the field of monetary means. For the time being, let's just note that the question is quite similar. But the US dollars, and new US TBills still enjoy a large credit worldwide.

Forecasting and budgeting

This leads naturally to a second principle: keep

constantly track of forthcoming expenses, and keep forecasting as well as you

can future cash inflows. This process is called budgeting. By the way, do not confuse a sale with a cash inflow.

Don't mix up a profit and a cash inflow either. We may very well have made a

profit, in the books, and yet be short of money. It is a frequent danger for

fast growing new firms.

Different categories of expenses. Current expenses,

capital expenditures

In this example we saw the difference between several

types of expenses: the expenditure to purchase a mechanical saw is of a

different nature from the travelling expenses for the month of September.

Accounting will treat them differently. Within "current" expenses we also see

many differences: the purchase of wood is of a different nature from, for

instance, the monthly expenses for telephone, or the salaries. All these will be

carefully recorded separately by the accounting system.

Expenditures for equipment like a mechanical saw or a desktop computer or a delivery van are called "capital expenditures" (the etymology of the word "capital" refers to cattle heads!). These pieces of equipment are tangible and remain within the firm for several years. They become what we call "fixed assets of the firm".

Expenditures, like salaries of the month of September, or travelling expenses, or the monthly rent etc., are not "capital expenditures". These expenditures are of another nature. They correspond to some sort of "consumption", just like when you buy yogurts, or pay your piano teacher, as opposed to when you buy a bicycle. The name used in accounting for these "consumption expenditures" is "revenue expenditures". Salaries or rents do not end up as assets of the firm. (Every rule having exceptions there are some exceptions, but they are not important for the moment.)

A sale which brings no cash

After a few months of efforts we win a sale to Carrefour. That is, we get an

order from Carrefour. We ship the next day, or a few days later 2000 toys to

one of Carrefour's warehouses. On that day we cease being the owner of the toys.

The ownership is transferred to Carrefour. In exchange for the toys we do not

get money yet. We get an IOU of 20 000 € to be paid in 45 days, that is, in 45 days, we

shall receive the money in our bank account..

Carrefour's promise

This IOU is interesting. It replaced 2000 toys out of the 3000 toys that we had in our

firm, waiting to be sold. This IOU is an asset of the firm. It is not money, but

it definitely has value. Since Carrefour is a very big firm, very well known,

and very trustable, there is no question that our IOU will be transformed into

20 000 € in a month and a half. This is because Carrefour is

"trustworthy". You need time (and a good track record) to build

creditworthiness. There is no way to build creditworthiness (or, simply,

confidence) quickly. Carrefour is creditworthy; our firm has not proved its

creditworthiness yet.

When to extend credit?

Whenever we exchange something coming from our firm for

something else coming from somebody else, we have to make sure that what we receive has the value we are told. Sometimes there is no question (eg.

Carrefour). Sometimes it requires trust (= faith) on our part. For instance, if a new unknow client

wants to buy 1000 toys, receive them in one week, and pay in two months, do we

accept to ship him? We may

accept or we may not. Usually we require new clients to pay first when they order, and

after a while, if they appear to be serious, we may apply a more flexible "payment

policy".

Credere

When we trust a potential client, we shall accept an IOU promising a payment in one month or in two months. We

then "extend credit" to the client. "Credere" means "to trust" in Latin.

"Credit" will appear again and again in commerce and therefore in accounting and

in finance.

Promises. Money. Public promises. Private promises.

Commerce has to do with confidence, trust, faith, credit. As soon as we

receive something else than pure merchandises in exchange for the goods we sell

- that is, as soon as we leave barter -, we need to have confidence in the means

of payment we receive. It can be an IOU from a client; it is equivalent to

private money. Or it can be official money (in our region of the world, the

euro), that is legal tender. By law, in the euro zone, you cannot refuse payment

in euros to extinguish a debt. It is public money; but, still, it requires some faith to

accept it. What if the purchasing power of the euro goes down? (And this is a

moot question considering the budget deficits that Germany and France run these

years, or the difficulty of Europe to prove a powerful integrated economical as

well as political area.) Of course, as

long as you don't keep too much euros, and never hold them for too long, you don't

have to worry. But then you have the problem of how to store the surplus value you

created.

Commerce means exchange

"Commerce" means "exchange", "social

intercourse". This is one of the reasons why doing

business is so interesting: not only, if we're successful, do we make plenty of

money:-), but we constantly deal with people and have to evaluate who is

trustable and who is not. It is great fun for he who likes human contacts.

Monetary and non monetary information

Accounting is concerned with the recording of all the events or information

of a monetary nature happening in the firm. Managers need to constantly monitor

this information to manage correctly their firm. That is why

we say that Accounting provides a dashboard of the firm.

What managers do?

It is not the only one. Managers must also

monitor plenty of information that is not of a monetary nature: productivity of

workers, downtime of equipement, creditworthiness of clients, contracts with

salaried people, quality of raw materials, worrisome delays in

delivery, should we change supplier?, the problems created by changing supplier,

the market tastes change, a competitor has a production process with much less

waste than us, there will be a surge in demand in the Fall for the Christmas

period, how to accommodate this inflated order log? etc.

The origins of modern accounting

Why double-entry accounting is so much better than

single-entry acccounting?

Single-entry accounting

Why did Venetian merchants invent double-entry accounting? From a little example using the booklet contained in our checkbook, we will

understand why single-entry accounting is not well adapted to recording value

movements in transactions, particularly commercial transactions, and why

Venetian merchants devised a more powerful method. Our common checkbooks have a little booklet, at the beginning or at the end,

in which we keep track of the checks we wrote and of our current bank balance.

Here is what it may look like:

| Previous Balance 250 € |

||||

| Number | Date | Description | Euros | Balance |

| 107 | Oct 10 | School club fees for the semester | 50 | 200 |

| 108 | Oct 12 | Electricity for August and September | 23 | 177 |

| Oct 14 | Money from Grand'Ma | + 60 | 237 | |

| 109 | Oct 15 | Scarf for Mary | 25 | 212 |

We record the checks we write, and compute the on-going balance. As we can see, we can also record money coming in our bank account with this booklet (money from Grand'Ma). It is not precisely designed for that, but why not?

In our bank account we rarely go down to zero. We could. We could even go to a negative balance, it all depends what agreement we have with our banker. When we go negative, we have to pay agios (bank charges) to the bank.

This is called single entry accounting: for each movement, we make a single entry that describes it and records the value of the check or of the money coming in (and, for convenience, we compute and note the resulting balance of our bank account). Accounting was done this way, and only this way, since about 3000 bc until sometime after 1000 ad.

First scriptures

The first scriptures, that appeared about 3000 B.C.

in Sumer civilization (with the cuneiform characters), in the Middle East,

were accounting records. They recorded the number of cows owned by some rich

people, or the quantity of wheat purchased by the king, etc. The other early

writings were epics and law codes (the Gilgamesh epic, the Hammurabi law code,

etc.). Geographically, Sumer was located where is today Southern Iraq.

The location of Sumer

Source:

https://www.hyperhistory.com/online_n2/History_n2/a.html

Herodotus definition of History

Since, following Herodotus, we define the beginning of

History as the date of the first writings, we can say that Accounting is exactly

as old as History. And this makes sense because writings were invented to keep a

durable record of important facts in society. These important facts were what we

owned, what we exchanged, the rules to live together, and the story of our

people.

The limitations of single-entry accounting

Single entry-accounting is not handy to keep track of all values. Let's try

and illustrate why. Suppose that on Oct 16 we do for 80 € of work for Joe. Now Joe owes us 80 € but

he will pay us in, say, only 15 days. What entry to make in our checkbook?

- Enter +80 euros in the "Euros" column, and a new balance of 292 €? No, that would lead to confusion.

- Enter nothing? But we know that in 2 weeks we shall get 80 € from Joe. We want to make a note of that.

We can refine the example: our balance on the 16th is 212 €. Suppose we need to pay 250 € on October 20th. What to do? We may write the check number 110 and ask the recipient not to cash it until we receive Joe's payment.

- What is our balance after check numer 110?

| Previous Balance 250 € |

||||

| Number | Date | Description | Euros | Balance |

| 107 | Oct 10 | School club fees for the semester | 50 | 200 |

| 108 | Oct 12 | Electricity for August and September | 23 | 177 |

| Oct 14 | Money from Grand'Ma | + 60 | 237 | |

| 109 | Oct 15 | Scarf for Mary | 25 | 212 |

| Oct 16 | Work for Joe (80 €) to be paid to us at the end of the month | - | 212 | |

| 110 | Oct 20 | Rent for the months of august and september (250 €), but we asked the landlord not to cash the check until the end of the month... | 250 | ? |

What we see is that if we want to keep track of our "financial position", taking into account money that will come in, and money that will go out, our single entry checkbook is not sufficient. We have to make all sorts of notes around the main column "Euros", and the balance of our checking account is only one piece of information among a more elaborate set of figures which we want to keep track of.

Same problem for medieval merchants

The same problems mired the single entry

accouting system of merchants. So they invented a more efficient accouting

system, called double-entry accounting. And it proved so efficient that it

is still used today, not much modified from 800 years ago! We shall see that it

is a system which solves very nicely the problem of money owed to us but to be

received later, as well as payments that we will have to make in the near future

for things already received. Double-entry accounting will also play many more

wonders: it will produce a complete and very useful dashboard of the

firm, in monetary terms. At any point in time, we will know "how we are doing",

and we shall be able to appreciate "how we performed" over any period of time t1

to t2.

Creation of other accounts.

Back to our checkbook: instead of covering the

booklet of our checkbook with notes about money due and money to be receiced in

the future on the pages where we keep track of checks and cash balances, we

shall make these notes on other pages, not on the cash booklet. These

other pages will be other accounts.

The booklet will be used only to record movements of cash (or in the bank account). It will be the cash account.

Other movements of value will recorded on other pages of a big book (that will be called the ledger of accounts). These other pages will be other accounts. Each account will try and record movements of value of the same nature.

Single-entry accounting is only concerned with cash

Single entry accounting is only concerned with cash, and cash

movements, and therefore is rather simple: some cash comes in, we record it;

some cash leaves, we record it; and we always know our cash position.

Double-entry accounting is primarily concerned with

value

Double entry accounting was designed with the objective of keeping track of

value, and not to mix up the various types of values (essentially three

types: cash, promises of future payment, and tangible goods). This is the

reason why it is more complex than single entry accounting. But it is also much

more powerful. And not only does it enable us to have a synthetic view of what

we own (our "assets"), but also of what we owe (our "liabilities" to external

agents). The difference is our "net worth", which in double-entry accounting is

also recorded as a (special type of) liability. All these appear in a document

called "the Balance Sheet". Double-entry accounting also produces a very useful

document presenting the creation of value via the operations of the firm over a

period of time: it is called "the Income Statement". The next few lessons are

devoted to learning in detail how these documents are established and how to use

the information they present.

Where accounting information is recorded (1)

The checkbook booklet will be limited to

recording movements on our bank account. Other monetary information will be

noted elsewhere. The piece of paper on which we will keep track of work done for

Joe, and what he already paid, and what he has not paid yet, will be called "Joe's

account". And we shall see, in a minute, how we technically keep this account.

Where accounting information is recorded (2)

Said another way: when the money movement does

not take place at the same time as the corresponding operation (for example,

doing some work for someone, purchasing a product, or a service that we shall

actually pay for later, etc.) we need to make recordings elsewhere than in our

checkbook booklet.

Accounting is only classification

Remember: keeping an accounting system is

nothing more than classifying monetary information, a bit like how we classify our

incoming e-mails into various specific folders instead of keeping them all in one

single "incoming mail" folder.

Principles of double-entry accounting

Transactions

Venetian merchants realized that every elementary operation they made was a

transaction where at the same time some value left their firm and some

value entered their firm.

When we sell toys to Carrefour, we do not receive money payment at the same time, but we do receive at the same time some value: an IOU worth 20 000 €.

The two legs of a transaction happen and are recorded

at the same time

That is the crux of the matter: in double-entry accounting we will always

record two movements. There will be a record of value leaving our firm, and a

record of value entering our firm, at the same date.

The recorded values of the two legs are equal

These values will be equal; it is another of the principles of

double-entry accounting. The profit made on selling the goods will be recorded

via some sort of a trick: the invention of the Sales account, and of the Cost

of Goods Sold.

Why is a column called debit?

Secondly, when a client (let's call him Berthold) of our Venetian merchant purchased some goods but

paid only with an IOU, the Venetian merchant naturally recorded that part of the transaction in an

account named "Clients" and he made a note in a column called "debit"

(because Berthold is a debtor). And in

another account he recorded what left his firm.

Why is another column called credit?

Similarly, when he purchased something on credit, he made a note in an

account named "Suppliers" of the money he promised to pay. He noted the

monetary figure

in a column called "credit". And in another account he recorded what arrived in

his firm.

When his client, Berthold, paid him, he "cancelled" the debit by noting further down, on the same sheet, that the client sent him money. Remember that in the XIIth century modern algebraic signs were not invented yet (the minus sign was invented in the XVIth century). So the merchant noted the payment of his client in another column, in the same "Clients" account.

The two columns debit and credit are sufficient to do

all the recordings

Then, these inventive Italian merchants realised that all their accounts could

be kept with only two columns, one of them working like the debit column of their

clients account, and the other one working like the credit column of their

suppliers account. For instance, when the client Berthold paid it was like some figure

accumulating in a "credit" column, and in fact if the client paid too much, he

would become a creditor, etc. So, naturally enough, all their accounts were kept

with the same layout. Example of account:

| Clients account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

01.09.2005 20.09.2005 15.10.2005 |

Sale of silk to Berthold. Sale of spices to William. Berthold settles his account. |

2000 |

|

Of course they could also keep separate accounts for each client, if they needed finer information.

The debit and credit columns of each account:

A debit is recorded somewhere for any value entering

the firm (and a credit is recorded elsewhere)

Noting that a promise from a client is a value entering their firm, and is

noted in a debit column, the Italian merchants extended this principle to any value entering

their firm, a van, a piece of equipment, even the right to use premise for a

period of time, or the work of an employee.

A credit is recorded somewhere for any value leaving

the firm (and a debit is recorded elsewhere)

Similarly they noted that when they give a bill of exchange (a promise to

pay at some future date) to a suplier, it was value leaving their firm, and it

was

noted in a credit column. So they extended that to any value leaving their firm,

even cash.

Therefore the cash entering their firm is recorded in a debit column on the page called "the cash account", and cash leaving their firm is recorded in a credit column on the same page.

When we must record who pays us?

Cash entering our firm is not much different from a promissory note entering

our firm: it is value entering our firm. There is one substantial difference

though: cash is money, a draft (or promissory note) is not. When we receive cash

we don't need to write on the "bank note" who we got it from; whereas when we

receive a promissory note we must record whom it comes from, because that person

will have to transform it into cash for us at some agreed upon later date. Whence

the saying: "money has no smell".

They discovered that all their accounts could be kept tidy and meaningful with these two columns.

The trick of the Sales account and COGS

account (1)

They invented an account called "Sales account"

which seems strange at first: it is credited when they make a sale, and

whatever account receives the payment is (as we already saw) debited. The idea is this: since they want to apply strictly the rule "the two movements of a transaction must have the same monetary value", they cannot, when they make a sale, simply debit the cash account and credit the inventory account, because the two values are different (one is at "selling price", the other one is at "inventory price"). So they created this artificial "sales account" which is credited at the same time as the cash (or any other money) account is debited. And they did something similar for the movement out of inventory (next item).

The trick of the Sales account and COGS

account (2)

Similarly

they invented a COGS account (I use modern terminology) that is debited when

goods leave the inventory of their firm, that is when the stocks are credited. The sales

acccount and the COGS account are therefore a bit special; it can be viewed as some sort of a trick to

follow the rules of double-entry accounting, and - at the same time - be able to

compute a gross margin: Sales - COGS.

The breakthrough of recording value

movements on top of cash movements

It can be said that the big breakthrough achieved by Italian

merchants of the XIIth century is that they ceased to measure only movements of

cash in their firms to measure movements of value. It is conceptually

much more powerful, although it does lead to a more involved accounting process.

Cash remains the ultimate measure

And cash remains the ultimate value that determines if a firm is

healthy or not. If we cannot pay with cash a bill that comes due, we go bankrupt.

The functioning of value and of cash is full of deep questions. We shall discover them little by little.

Going into the nuts and bolts of double-entry accounting

All the information is contained in the journal

We start from the journal, as always. All the monetary

information to manage a firm is contained in the journal. The only problem with

the journal is that it is too big, it is not organized, it is not synthetic. It

is not convenient to see very quickly "how we're doing", and to take the

appropriate decisions.

The journal is descriptive, not organized, nor

synthetic

The journal records the transactions, in a descriptive as well as

quantitative way, one after the other. Each transaction is an elementary

operation of the firm. That is why I like to call it "the atom of activity" of

the firm.

An example

Example of journal entries at the beginning of a firm

(a firm founded by Joe):

- On January 1st 2005, Joe started his business with £5000 in cash. He puts the sum into a cash box.

- January 3rd, he takes £3000, out of the cash box, to put them in a bank account.

- January 3rd, he (that is, his firm) purchases a van, £2000 paid by check.

- January 7th, the firm buys some goods, £1000 paid in cash.

- the 9th, the firm sells some goods, for £1500, received in cash.

- On the 31st, the firm pays a salary of £1000 to Joe.

In order to really understand what's going on, some preliminary comments must be made.

Joe's firm's money is different from Joe's money

First all, Joe decided to found a firm. It will be

important to distinguish Joe and his firm, called Joe's firm. Joe's firm is

different from Joe, the person. And Joe will have two roles: he is the owner of

the firm, and, in this little example, he is also an employee of the firm.

Pure trading, or manufacturing and selling

Secondly, the business Joe decides to enter consists in

purchasing goods and selling them to clients without any transformation in

between. For example, Joe's firm is a clothing shop: it purchases cloths and

sells them. It is not like the Chinese snake manufacturer that sold toys, but

purchased wood and tape and glue. The clothing shop purchases its goods from a

dress manufacturer.

| Clothing shop | |

| Goods purchased | Goods sold |

|

|

| Manufacturer of dresses | |

| Raw materials purchased, and equipment | Goods sold |

|

|

It is simpler to study the accounting of shops that purchase and sell goods with no intermediate transformation. Shops do have a "value added" too, but not as concrete as that of manufacturers.

Shops do add value

Typically the clothing shop will buy dresses £50 apiece and sell them £100 apiece. It looks like a wonderful business, where we

don't have much to do. But it is not quite that simple. It is possible to earn a good living running a shop, but it is also easy

to lose a lot of money.

Joe' money and Joe's firm's money

Comment number three: once Joe has put £5000 into the cash box of his firm, this money now belongs to the firm, no longer to Joe

directly. (The firm itself belongs to Joe, OK.) There are legal rules about what a firm can do with its money and what it cannot do. These rules are different from

what Joe can do with his own personal money.

The cash box and the bank account of the firm

We shall distinguish the two places where the firm keeps its money: the cash box (also called the till, or the cash register),

and the bank. We shall keep a separate account for each. If you stand for a while in front of a shop, you may see the manager of the

shop stepping discreetly out of his shop, with a folder under his arm, and going

to the bank nearby. In his folder he has cash, that he is taking to the bank in

order not to have too much cash on his premises. Once again: do not mix up Joe and his firm.

An anecdote illustrating the importance of distinguishing

the firm from its owner:

I once had a business in publishing and I was renting from

a landlord who also had a publishing house, "Les Editions Entente", in the same

building on the floor beneath my office. He wanted to sell his business, and

thought of me. He asked me whether I was interested in buying "Les Editions

Entente". I said: "Why not? Can I see the accounting documents?" He gave them to

me. They showed a turnover of 2 million French Francs, and a profit of 300 000

French Francs. A pretty good performance! I look more closely at the accounts

but couldn't see the rent. I asked: "Your firm doesn't pay rent?

- No, the building belongs to me.

- Well but there should be a rent. In fact the figure

would be about 300 000 French francs. In truth your profit is 0."

He looked at me with eyes looking like plates. To try and

make him understand that he was making a gift of 300 000 French Francs per year

to his firm, which explained the profit, I asked him: "If I purchase the firm

from you will there still be no rent?

- Oh no, in that case you will owe me 300 000 French

Francs per year."

He was mixing up the accounts of his firm and his own personal accounts. He thought that he was selling a highly profitable firm (therefore worth a lot of money) when he was actually selling an unprofitable firm. A firm making no profit, in most situations, to any buyer, is worth about nothing*. Someone could argue: "But it can pay you a salary!" Yes but you don't need to purchase the whole firm in order to sell your work. In fact this is an interesting question in the economics of work markets, that we shall not address here.

When we say that Joe puts 5000 pounds into his firm it means that afterwards Joe has 5000 pounds less of his personal money, and his firm owns 5000 pounds. And from now on what we are interested in is what the firm does with its money. We are no longer interested in Joe's personal money. If later on we sometimes say "Joe purchases a van", it is a misleading way of speaking: it is Joe's firm that purchases a van.

In these simple businesses the owner usually is also employed by the firm, so the boss may receive a salary for his work. In our example Joe will receive a salary of £1000 paid at the end of each month. This salary is paid to Joe because he works in this firm. You don't pay salaries to shareholders, you pay salaries to workers in the firm, that is to people who sell their work to the firm.

* We shall see later in this course how we approach valueing a firm. It may have different values for different acquirers, being worth nothing to some, but being worth something to others, because the value of a firm depends not only on the firm itself, but also on the potential buyer's activities.

Let's begin the accounting treatment of the journal entries:

I will describe what is done nowadays. I will not try to explain step by step how it developed historically over a couple centuries in the late Middle Ages (XIth to XIIIth centuries). So, for a little while, we shall get a bit technical and then, retrospectively, the logic will be crystal clear, but not necessarily at first.

The first entry of the journal is "On January 1st 2005, Joe started his business with £5000 in cash. He puts the sum into a cash box." We reorganize it into two accounts:

1a. In a first account, called the capital account, we record the founding money and who it comes from. The account looks like this (all accounts have exactly the same structure):

| Capital account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 1.1.2005 | Initial capital coming from Joe paid in cash. |

5000 |

|

The entry is made on the credit side. Joe becomes someone who gave something to the firm and is recorded as such. The capital account is the piece of paper on which we record who the founding money came from, and only that information. What the firm will do with this money is another matter. It is not recorded here.

1b. In a second account (remember: an account is just a piece of paper on which we note things) we record that the firm receives some cash. This second account is called the cash account:

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 1.1.2005 | Initial capital coming from Joe paid in cash. |

5000 |

|

Every operation described in the journal gives rise to two entries in two different accounts, and one is in the credit column and the other one in the debit column. It is this mechanism which was designed by merchants 800 years ago, and turned out to be very powerful in recording what happens to the firm.

So in the Cash account, we record £5000 in the debit column. We shall see in a minute why it is logical that it be recorded on the debit side.

For a little while, in this course, I'll distinguish cash on the premises of the firm and money at the bank. Then the two will be treated as a lump sum of money.

Accountants are very tidy, to the point of being nitpicking, it is necessary to keep correct accounts when there is plenty of information to classify. Anecdote: the etymology of the Sergent Major pen.

Let's turn now to the recording of the second transaction into two accounts.

The second transaction is "January 3rd, Joe takes £3000, out of the cash box, to put them in a bank account".

2a. First of all we record a movement in the cash account. It had £5000 after transaction 1. Now £3000 will leave the cash account.

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

1.1.2005 3.1.2005 |

Initial capital

coming from Joe paid in cash. Money taken from the cash account to be put in the bank account |

5000 |

|

The £3000 that leave the cash account are now recorded on the credit side, that is the other side from recordings of money coming in. This is logical: this way we readily see that what remains in the account is £2000.

For the "description" accountants also have rules. But in this informal presentation we need not be concerned.

2b. And, every transaction giving rise to two entries into two different accounts, we now have to make a record of what happened to these £3000 that left the cash account. They arrive into the bank account. So (always our concern to keep track of information, and classify it) we take a new sheet of paper, call it the "Bank account" and make a recording in it.

| Bank account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 3.1.2005 | Money taken from the cash account and put into the bank account |

3000 |

|

Once again here the value (belonging to the firm) arriving into the bank account, it is "debited".

Rule: The information of every transaction recorded in the journal will be reorganized into two accounts (one on the debit side, and the other one on the credit side). That is why this modern accounting technique is called "double-entry accounting". This rule has no exception.

Remember: a transaction is an elementary

operation involving the firm and the rest of the world where money or

value changes hands.

Examples of transactions:

- a banker lends money to the firm

- the firm purchases some goods

- the firm receives money from a client for a sale made earlier

- the firm pays a supplier

- the firm uses some raw materials to manufacture a product

In all these examples, some money or some value changes hands.

Examples of operations which are not transactions :

- the firm hires a new employee

- the production manager sets up of a machine

- a salesperson visits a prospect

- a driver takes a truck to the garage

The bank account in our system, and the bank account of the firm in the bank accounting system:

Why debit and not credit the bank account? Everybody knows that when we

receive some money and put it at the bank we say that our account is credited

(cf. for instance "Trois jours chez ma mère", by François Weyergans,

Grasset, 2005, page 55). The origin of the casual saying, and of the

confusion, is this: when we have more money at the bank, we are a more

important creditor of the bank, that is, in the bank accounting system

our account is in credit, and the more money we have the more in credit it is.

But this is in the bank accounting system. If we had a personal accounting

system, everything would be reversed: the bank account, in our

accounting system, would debited, and the more money we had the more in debit it

would be.

Cash on the premises and money at the bank

For the time being, I distinguish Cash and Bank (soon the two accounts will

be lumped together). So there are three ways to receive value in our firm:

cash, cheque, and promisory note. I leave aside receiving some part of the

stocks (i.e. value) from a firm which can no longer pay. This situation arises

once in a while, but is neither common, nor entirely legal. On the other hand,

barter in international commerce is frequent, with countries short of strong

currencies..

Treatment of the third transaction

The "treatment" of a transaction, consisting in classifying the information into two accounts, is called "posting".

The third transaction record in the journal is: "January 3rd, he (that is his firm) purchases a van, £2000 paid by check".

In this transaction value (a van) will enter the firm, and money (by check) will leave the firm.

3a. For recording the money leaving the firm by check we already have the account: the bank account. So we make the new entry shown below :

| Bank account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

3.1.2005 3.1.2005 |

Money arriving in

the bank account coming from the cash box Money leaving the bank account to pay for the van |

3000 |

2000 |

Note that in the descriptions above only the part in bold is useful

information. For the first line, we already know that it is money coming in the

bank account because it is on the debit side. And for the second line, we

already know that it is money leaving the bank account because it is on the

credit side. So the standard (and rather terse) descriptions are:

for the

first line: cash

for the

second line: van

3b. For the second half of the double entry posting the purchase of a van we need a new account: an account where we record purchases of transportation equipment. Let's call it the "transporation equipment account"

| Transportation equipment account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 3.1.2005 | Purchase of a van paid by check |

2000 |

|

Transaction number 4: " January 7th, the firm buys some goods, £1000 paid in cash"

Like for any transaction this describes a movement of value: goods come in the firm, and cash leaves the firm.

4a. Let's start with the transaction half for which we already have an account: cash leaving the firm

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

1.1.2005 3.1.2005 7.1.2005 |

Initial capital

coming from Joe paid in cash. Money taken from the cash account to be put in the bank account Cash leaving the firm to pay for goods |

5000 |

|

Here we pay for the goods with cash (the simplest way) so the recording is very simple: the cash account is credited £1000

Note, by the way, that it was possible to pay £1000 with cash, but it would not have been possible to pay say £2500, because the cash account cannot have less than zero money in it, just like my pocket can have money or can be empty, but cannot have less than zero money in it.

This remark does not apply to the bank account. With proper agreements with our banker, we can "have less than zero money" in our bank account.

4b. Goods enter the firm. We don't yet have an account for goods in the firm, so we open a new account, and record that the firm receives goods. We could call this account "Purchases of goods account" but the custom is to call it "Purchases account".

| Purchases (of goods) account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 7.1.2005 | Goods (for resale) entering the firm (paid with cash) |

1000 |

|

In a shop the "goods" is the name given to products purchased for resale. Dresses are goods in a cloth shop, shelves are not.

A large "expenditures account" is not a good idea

We could be tempted to record the goods purchased

into a large account called "things purchased" where we would also record the

van, office equipment and everything else purchased. This would not mess up the

arithmetic of accounting, but it would definitely mess up the usefulness of the

information we are creating. This is just like the process of classifying our

e-mails: if we have too big a category "other e-mails" it is as useless as

having no folder classifying system at all for our incoming e-mails. That is why

we do not record purchases of goods in the same account as acquisitions of

equipement (and we distinguish in different accounts the different types of

equipment).

Transaction number 5 : "the 9th, the firm sells some goods, for £1500, received in cash"

The most important transactions in a firm: sales !

Here the transaction is: goods leave the firm as sales, and money (in the form of cash) enters the firm. Let's start with the part of the posting for which we already have an account

5a. £1500 of cash enter the firm

| Cash account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

1.1.2005 3.1.2005 7.1.2005 9.1.2005 |

Initial capital

coming from Joe paid in cash. Money taken from the cash account to be put in the bank account Cash leaving the firm to pay for goods Cash from sales |

5000 |

|

Note that this transaction does not specify how much of the goods present in the firm where sold in this selling transaction: presumably about £750 worth of goods (at purchasing price for the firm), but it is not recorded here.

Traditional shops dislike to tell clients their purchasing price. And they dislike even more to tell their clients who is their supplier (although usually it is not very hard to figure out). But note that suppliers who accept to sell directly to final customers irritate their distribution network. They end up loosing it, and then they have to enter the business of distributing themselves their products to final clients. They discover that it is a different activity from selling to shops. It is called "downward integration".

5b. Sales. We need to open a new account: the "Sales account"

Because of the rule of double entry accounting, "in every double entry recording one account is debited and another one is credited", the sales account is going to be credited (because the cash account was debited).

| Sales account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 09.1.2005 | Sales of goods paid in cash |

1500 |

|

It is always a bit difficult at first, when studying accounting, to accept that "a sale is a credit". We shall discover little by little the deep logic for this. The best for the time being is to carve it on stone in our mind: a sale is a credit.

Sixth transaction : "On the 31st, the firm pays a salary of £1000 to Joe."

Like every transaction, this transaction records a movement of money or value: money leaves the firm in exchange for one month for work consumed by the firm.

Cash or check? Good question. The recording in the journal is flawed: it should have specified cash or check. Let's go to the payroll office and ask them: the tell us it was paid by check. OK. So we shall credit the bank account, and debit a new account "salary account"

6a. Credit the bank account for paying Joe at the end of the month

| Bank account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

|

03.1.2005 03.1.2005 31.1.2005 |

Money arriving in

the bank account coming from the cash box Money leaving the bank account to pay for the van Money leaving the bank account to pay Joe salary |

3000 |

|

6b. Open a new account recording salary payments

| Salary account | |||

| Date | Description |

Debit |

Credit |

| 31.1.2005 | Joe salary for the month of January (paid by check) |

1000 |

|

A caveat: when a bank says informally to you:"we will credit your account with $100" and you "receive" $100, it seems that the rule "value received = debit" is invalidated. But it is not. What they mean is that in their accounting system they increase a credit column in an account at your name. But if you kept a full-fledged accounting system for your own economic situation, you would debit an account receiving value (and you would credit another account, like "sales" or "subventions received", or whatever, as the counterpart of that transaction).

Break time