Advanced finance

Lesson 2: Banking systems, foreign-exchange markets, off-shore currencies

Currencies

Currency zones

The world is divided into currency zones, corresponding to developed countries and their areas of influence. There is the dollar zone, the yen zone of Japan, the yuan zone of China, the pound zone of Great Britain. Since 1999, after a long gestation, several

European countries created a new currency, the euro, and formed the eurozone. And there are other less important currencies.

Untying currencies from gold

From the Bretton Woods agreements of 1944 until 1971, the dollar was the world dominant currency within an

organized world monetary system resting on fixed exchange rates between the dollar and other currencies, and ultimately on the convertibility of the dollar into gold guaranteed by the US at the rate of 1 oz of gold = $35. In August 1971, because of the large volume of dollars abroad that could come back at any time to the US and ask to be converted into gold, and the relatively low gold reserve of the US, President Nixon decided to "close the gold window", that is to abandon convertibility.

Attempts to maintain an organized system of currencies

After 1971, developed countries tried to maintain an organized system of currencies and exchange rates (Smithsonian agreement 1971, Jamaica 1976, Plaza 1984, Louvre 1987).

Dollar in international trade

The dollar remained the world dominant currency, used in international trade (oil, raw materials, manufactured goods, travels, etc.), but currencies essentially "floated" with respect to each other (example: French Franc versus Dollar). In the 1970's, gold experienced a fantastic price increase (to $850 in January 1980), followed by a 20 years decrease, and then, since the beginning of the years 2000's it is rising again.

The present day unsatisfactory situation

Today's situation is still unstable. Some important countries, like China, control the exchange rate between their currency and the dollar; they prevent by all available means foreigners from holding yuans and carrying transactions in yuans, and they prevent most Chinese citizens from holding foreign currencies; so they control the exchange market between the Chinese currency and the rest of the world currencies. Some others, like the eurozone, let their exchange rate evolve according to market forces (example: Euro versus Dollar).

Triffin's paradox

In 1960, Belgian economist Robert Triffin, 1911-1993, pointed out that the Bretton Woods agreements, giving prominence to the dollar in international commerce, would necessarily lead to a growing trade imbalance between the US and the rest of the world, since the world would need a growing supply of dollars to accompany its economic expansion. This prediction has been verified, beginning when the dollar, in 1971, ceased to be tied to gold.

To live with $2 per day ?

When we learn that 3 billion people in the world live with $2 per day or less, we must avoid a misunderstanding. Of course these people belong to the Third world and are poor compared to the standard of living in the West, but they are not as poor as the figure, taken at face value, would suggests. Remember that currencies are abstract measurements of value. In a given geographical area, if you earn only the equivalent of $2 per day, but need only the equivalent of $2 per day to buy what you need at local markets, you can lead a sustainable life. Moreover, regions where people "live with $2 per day" are regions where monetary exchanges still represent only a fraction of exchanges - just like western countries until the XIXth century. True, if you earn $2 per day, you cannot buy a new DVD reader costing $100, but you can usually buy the food and clothing which you don't produce yourself, and you can have a dwelling, which you only pay a small price for.

More misunderstandings to clear

We shall discover little by little that "money" is much more abstract and more elusive than we have usually been accustomed to think. The following facts are counterintuitive but true:

- the flight of capital from one country to another is not "some value which was 'working' inside a country and that now goes out"

- the "lack of capital" in one country is not what common sense pictures; it is not directly related to a low (or negative) saving rate; conversely a positive saving rate doesn't automatically produce the capital needed for investment

- if Europe borrowed money from the US after WWII, for reconstruction, it is because its monetary systems still rested on gold, and Europe lacked gold then (it had used it to pay for US help during WWII)

- since the 1980's, the US actually consume capital from the rest of the world (about $2 billion everyday for the past few years)

- anyone anywhere can borrow from somebody else, paying with an IOU denominated in dollars

- if the borrower (of the above item) is creditworthy, the IOU he issued can serve as a means of payment

- etc.

It is important to understand currencies. They are the official monetary units of each world country or zone. We shall see in the next section how official moneys are created and managed.

When we trade, how to get paid?

When we sell some manufactured goods from our country to another, how to get paid? In which currency? More practically: with what kind of value, or what kind of promises? How to make sure that what we receive as payment will keep while we hold it, before spending it, its purchasing power, and even possibly yield a profit? Eventually we may want to be paid in our currency (for instance to pay the salaries of our employees), but not always.

We shall study below foreign exchange markets, what they are, what purpose

their serve, how they function.

A new world currency?

China push for a new world currency

As of early 2009, China is pushing for a new world currency managed by the IMF. It would be somehow an extension of the SDR's created in the late 60's, to help the US who had balance of payment problems due to the Vietnam war and were running out of gold, but which were never used as an international currency. And it would be the realization of Keynes dream of the bancor, which he proposed at Bretton Woods, but was rejected by the Americans who prefered a system giving the central role to the dollar. The reason why China wants to go through the IMF (an institution with a poor track record, and a womanizer dilettante as its present director) is because it would be easier for her to bring its $1000 billion of US Treasury bonds to the IMF as assets to transform them into the new currency before they lose a large part of their value, than to another new "world central bank".

Why it will remain a dream

Even if the world managed to adopt one unique currency, it would not remain unique for long. Indeed the liberal system with no protectionism leads inescapably to some agents becoming very rich and other becoming very poor. Poor people or agents, can then devise some system to maintain trade within their community even if they have no hard currency. That is, new regional and local currencies will always pop-up. Another way to understand this phenomenon is to recall that a currency is only a vast system of pledges within a community. If some people run out of the currency they can always make up another smaller system of pledges. These smaller systems, be they LETS or other things, were always fought - or their development checked - by public authorities. But with the weakening of nation-states and public authorities that we foresee, new currencies are likely to appear, as we have already mentioned. And we believe they will be spontaneous, outside the control of nation-states, and more reliable than official currencies.

Banking systems

Monetary systems: a central bank and secondary banks

In all countries where a developed monetary system exists, there is a

banking system with two levels:

- at the top level there is the central bank, which oversees the whole

system

- at the bottom level there are all the other banks, also called commercial

banks or secondary banks (either retail or investment banks)

Firms, cities and individuals deal with secondary banks

Retail banks are those which handle the bank accounts of individuals and

firms. Investment banks are specialized into financing large projects of firms,

carrying out big bond issues, managing operations of merging and acquisition,

etc. (Sometimes the term "commercial" is restricted to retail banks, but in this lesson we shall use it for both, since they are now mixed.)

Separating, or not, retail and investment banks

During the great depression of the 1930's, the number of banks in the United States, due to failures, decreased by half, going from around 30 000 to 15 000. It was believe that the crisis had been aggravated by the mix of the two activities in the same banks. So in 1933, the United States passed a law called the Glass-Steagall Act which stipulated that henceforth the two activities should be carried out in different banks, presumably insulating retail banks, providing services to the population at large, from investment banks supposed to be serving only big investors and taking more risks. However, the act was eventually repealed by President Clinton in 1999. In 2008, in the wake of the "subprime crisis", and more generally of the inconsiderate risks taken by commercial banks, the question of going back to an equivalent of the Glass-Steagall Act is considered again.

A central bank manages the monetary system of its currency zone, and is the bank of secondary banks

The role of the central bank is to issue bank notes, to manage the money supply, and to oversee and manage the whole monetary system. We shall understand better this role when we study the balance sheets of a commercial bank and of the central bank.

The balance sheet of a commercial bank is familiar.

Depositors are creditors

Above is shown the balance sheet of a commercial bank. On the liability side

there is the usual capital plus retained profits, some possible borrowings from

other banks or bondholders, and the depositors. We saw that these depositors made deposits that

are akin to loans of money to the bank, but can also be created in exchange for

the creation of a new loan on the asset side. All sight deposit accounts at commercial banks are called "electronic money". It is important that you

understand very well the mechanisms of these various accounts.

Asset side: cash, reserves at the central bank, and

money working

On the asset side, we have, from bottom to top (i.e. from most liquid to

least liquid), a little bit of cash in the form of coins and bank notes (like

euro bank notes), then every commercial bank has an account at the central bank

(which is in credit at the central bank, just like your own account is usually

in credit at your bank), then some very liquid financial assets (like Treasury

bonds), then various loans to firms, municipalities, government agencies, and private individuals.

There are also (we haven't represented them) some physical assets like buildings

and equipment.

Banks make their depositors money work

As we see, the cash + holdings-at-the-central-bank (C.B. reserves) are usually smaller than

the depositors potential claims on the bank. This is at the heart of banking: since

it is unlikely that all depositors come to the bank at the same time to get "their

money back" (which is called a run on the bank), the bank can lend some of its

deposited money, while still ensuring that if you want your money back you can

get it from your bank.

Runs on banks

Runs still exist in our times. In September 2007, there was a

run on Northern Rock. And, in early 2008, Great Britain is refinancing and

nationalizing Northern Rock, to

the great dismay, in England, of tenants of strict liberal ("Thatcherian")

economics.

What is the proper amount of reserves?

The question of what is the proper level of liquid reserves that

commercial banks should maintain, with respect to their deposits, has been a debate

for at least two centuries. In the XVIIIth century, before the invention of "legal

tender bank notes", you will remember, banks kept 100% gold reserves

corresponding to their deposits.

The Bullionist controversy

Following the temporary suspension of convertibility in England during the

Napoleonic wars, the

Bullionist controversy arose between Bullionists (in favor of 100% gold

coverage), and anti-Bullionists (who said this requirement of 100% gold coverage

is a mistaken view of what money is; it hampers the proper management of the money

supply and in the end of the economy).

Currency school versus banking school

In the middle of the XIXth century, when the Bank of England was granted the

monopoly on the issuance of legal tender bank notes (in 1844), the controversy

evolved into the Currency school versus Banking school controversy. The Currency

school saying : "banks must keep a high percentage of reserves to cover their

deposits", and the Banking school, like the anti-Bullionists, saying: "this is a

misunderstanding of what the nature and the role of money are."

The three risks of banking:

- the imbalance between short term deposits and long term lending: most bank deposits are short term, while their loans are longer term. So there is the risk that depositors, having less trust in their bank, go and demand their deposits back. When this situation becomes extreme, it is called a "run on the bank", and can lead to its bankruptcy

- the credit risk: by definition the loans extended by the bank are risky. Some of them will default. When the default rate is too high the bank is in jeopardy. This happens, in particular, when banks have too much liquidities, and are lead to lend to less than highly creditworthy borrowers. This happened in Japan at the end of the 1980's. Then many big borrowers, and in their wake several big banks, defaulted (particularly in the real estate, following the burst of a bubble). It was also the trigger of the Asian crisis of 1997. And it is likely that the present "subprime crisis" (2007-2008), which is much bigger in size than the previous crises, will also have dire consequences on the real economy.

- the interest rate risk: usually interest rates paid to depositors are variable (and even when they are fixed, since the deposits are short term, the rates follow the market), whereas interest rates demanded on loans are fixed. When short term rates become very high, they can exceed loan rates. This is what happened in the late eighties and early nineties in the US, and it created large defaults in the Savings and Loans institutions, which required a big federal bail out.

Clients defaulting

One million American households have defaulted on their home mortgage payments since the beginning of 2007.

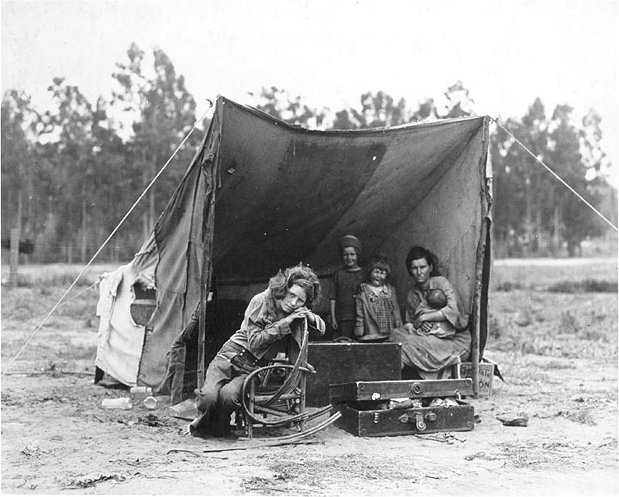

An American family which lost its home in the US in the 1930's

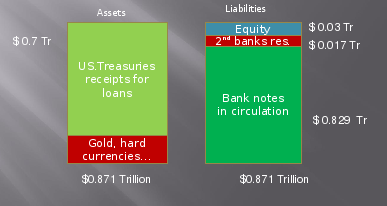

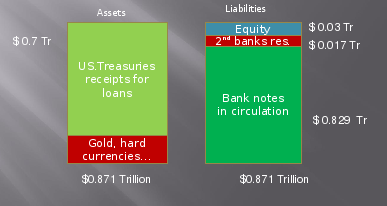

Balance sheet of a central bank.

Central banks were set up in the XVIIth, XVIIIth, and XIXth century (except for

the Fed, set up in 1913)

Let's now turn to the balance sheet of the central bank. Historically, the first one was the Bank of Sweden, in the middle of the XVIIth century, and the second one the Bank

of England in 1694. Both were created to receive gold to be lent to the monarch

to wage wars. A central bank is nothing more than a normal bank which received the monopoly to issue bank notes which are legal tender. So its balance sheet is not essentially different from that of any other bank. But since, the bank notes in circulation have a more official character they are usually recorded at the top of the liabilities, and the corresponding "permanent loans" to the Treasury (i.e. the till of the State) at the top of the assets. The two items don't necessarily exactly match, because Treasury receipts can be created matching reserves (i.e. bank accounts in credit).

|

|

|

Bank notes are recorded on top of the liability side

Above is shown a typical balance sheet of a central bank. On the liability side

we have the bank notes "created by the central bank" and which are in

circulation. They were at first "given to the government" (in exchange for the "treasury receipts", on the asset side; in French, "les avances de l'Institut d'émission"; in

clear, "la planche à billets", the "bank notes printing press"), and also to buy

some new bonds. Then we have reserves that commercial banks are required to

maintain at the central bank.

Secondary banks's reserves at the central bank

These secondary banks's

reserves, recorded as credits on the liability side of the central bank, can come from foreign currencies commercial banks got from

their clients and changed at the central bank for local currencies. They can also come from creation from scratch of loans by the central bank to the commercial banks, which will be recorded on the asset side of the central bank as well. This is how the Fed, since the Summer 2007, "injects" money into the US banking system.

As of September 2008, it plans to inject a further $700 billion in the US

banking system (a sum of the same order of magnitude as what has already been

injected). This can be from pure scratch loan creation, or from "buying rotten

debts" which commercial banks

held on the asset side of their own balance sheets. Since commercial banks, having then more reserves at the central bank, can create more money themselves, this central bank injection has a lever effect on the entire liquidities "injected" in the system.

Legal reserve requirements

There are legal requirements about the amount of liquid reserves (on the asset side) a commercial bank must keep in its assets (as cash and as reserves at the central bank) compared to the amount of deposits that can be withdrawn on demand. The usual ratio is 10%. A classical exercise is to calculate the effect of a $100 billion central bank injection, if the commercial banks are required to keep, say, 20% reserves in cash and at the central bank: in that case the total new money created by the commercial banks will be $500 billion.

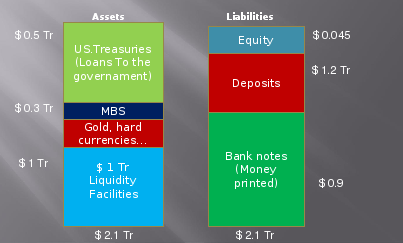

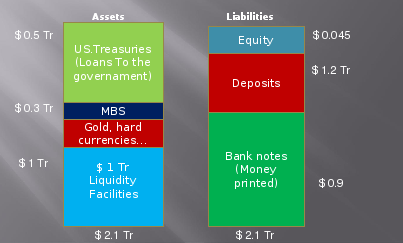

The balance sheet of the Fed

Here is the balance sheet of the Fed, before and after the beginning of the subprime crisis, which required huge injection of liquidities in the secondary banks.

Fall 2007

|

Spring 2009

|

We see that the "effort" to put money into the system (more than $1000 billion), is nothing more than bookkeeping entries on the asset side and the liability side of the balance sheet of the Fed.

Cooke ratios

On top of these legal reserve requirements in each currency area, in order to harmonize the measurements of banking security ratios worldwide,

the Bank of International Settlements, which was

created in 1930 in Basel, defined in the late 80's the

Cooke ratios. The main Cooke ratio stipulates that

[ Net worth of the bank / All assets weighted by their risk ] must be greater than or equal to 4%

Net worth = Capital + retained earning

The weights on the assets are:

- cash: 0%

- central bank reserves: 0%

- treasury bills: 0%

- loans: weights between 20% and 100% depending on their risk

- standard loans to individuals and to firms: 100%

- mortgage loans: 50%

- loans to states or municipalities: between 20% and 50%

Asset side of a central bank

On the asset side, the central bank has, going from bottom to top, some

international reserves (in currencies and in gold), Treasury bonds issued by its

government - these are used to carry out open market operations; and

the receipts by the government for the issuance of the bank notes

(in French "Avances de l'Institut d'Emission").

How to control the money supply?

Open market operations are one of the three major levers a government and its central bank have to manage the money supply (i.e. the quantity of money circulating in the country). These three levers are:

- modify the legal reserve requirements imposed to commercial banks

- change the prime interest rate paid by the government on short term funds lent to it

- sell some treasury bonds already held by the central bank (this decreases the quantity of bank notes and electronic money in the country), or buy some treasury bonds held in the population (this increases the quantity of bank notes and electronic money in the country)

Central bank money

The bank notes in circulation + the accounts of commercial banks at the

central bank (i.e. the entire liability side of the balance sheet of the central

bank) is called the "central bank money", or sometimes "hard

powered money" (see for instance Gurley &

Shaw, "Money

in a Theory of Finance", Brookings Institution, 1960)

Controlling

the quantity of monetary means

Beyond the apparent complexity of all these bank notes and other accounts, this whole banking system

of a country is just a system to control the quantity of monetary means in the economy

of the country issued by the various institutions having the capability to create money. These monetary means, we saw, are of several types:

- bank notes created by the central bank

- commercial bank reserves at the central bank

- treasury bills (and other bonds) issued by the state

- bills of exchange (and other commercial paper and liquid financial securities) created by firms

- bank accounts in credit at commercial banks (either from deposits of depositors, or by pure bank creation)

- foreign currency and precious metal holdings

- etc.

The legal reserve requirements, imposed on commercial banks by the authorities of the country where they operate, just contribute to exert this control on monetary means (i.e. money) creation.

"Money is not quantitative"

One of the theses of this course is that "money is not quantitative", it is

rather a system of signs of rights and liabilities. This change of paradigm has

tremendous consequences on the way to analyse money, finance and economic

activity.

Nation-states and their money

Within the geographical area where their authority can be enforced, governments impose legal requirements on the financial institutions. But

three phenomena are tempering these apparently strict protections:

- there exists banks escaping partially or totally national authorities (banks dealing in so-called

Eurodollars, and offshore banks)

- governments are the least responsible financial agents: central banks were made more and more independent of their government to avoid excessive creation of money via the printing press; but the limitless issue of Treasury bonds, in some countries, is not much different. Treasury and other government bonds are not legal tenders, but they are not liabilities of clearly identified agents either (who would have signed them); they "will be passed onto future generations". (Exercise: guess what will the future generations make of these "agent-less" liabilities ?)

- new moneys are appearing (which will escape entirely national controls, and be more and more useful)

Some thoughts on money:

We saw that money is an abstract unit of measure of value. And we saw, above, that a central bank "issues" bank notes, which represent rights to buy, of various denominations (10€, 20€, 100€, etc.).

One big problem of such monetary systems is that the purchasing power of the abstract monetary unit (and therefore of the corresponding bank notes, or even the accounts in credit) is not guaranteed to be stable.

Observe that the bank notes in the balance sheet of a central bank are at the same place as the capital of an industrial or commercial firm. In both cases they are on the liability side, and correspond to pieces of paper held by others (the population, for bank notes; and shareholders, for the equity of a firm). In both cases they represent a right to something:

- bank notes of 100€ represent the right to buy something worth 100€, but they say nothing about "what is worth 100€"

- shares of equity of a firm represent the title of ownership of a certain percentage of the firm, and they say nothing about the value of the firm (only the market decides what is the value of one share)

But shares are more concrete than bank notes in the sense that a percentage, say 1%, of a firm is more concrete than 100€, which correspond to nothing concrete guaranteed.

Shares of stock can be viewed as some sort of bank notes that would not be concerned with the monetary problem of stability of the purchasing power of the unit of currency.

Men tried to make units of currency buy something concrete - like shares of stock do - with the gold standard system, where units of currency corresponded to specific weights of gold. But gold is not itself "real value" or something producing value, and anyway any attach to gold was abandoned in August 1971. Since then, currencies are purely abstract.

Quentin Metsys, Le Peseur d'or et sa femme (1514), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Unregulated and off-shore banking

There exist banks that are outside the reach of the regulatory authorities of

countries.

In theory, anyone can start a banking activity

As we saw from a theoretical viewpoint in the previous lesson, a banking activity can be started by anyone who

owns initial reserves of liquid wealth (and we saw that even the initial "real wealth" is not mandatory, since

a central bank's initial capital, for instance, is usually made only of paper bank notes on the liability side, and Treasury receipts on the asset side).

This is one of the reasons why it is plausible to see in the future the

appearance of private international currencies, managed by more trustable

entities than state governments.

Banking and private paper money sprang up spontaneously

Indeed, since around the XIIth century until the XVIIIth century, banking and finance activities sprang up spontaneously. It was only during the Age of Enlightenment that national authorities began to organise and control their national banking system. Central banks with a monopoly of issuance of legal tender bank notes appeared only in the XIXth century.

Nation states and centralized systems

In fact the emergence of organized and state controlled banking systems parallels the emergence of nation-states with

centralized powers

in the western world (France, England, Spain, the United States, Germany, Italy, etc.).

The rise of "modern nation states" in the XIXth century

This banking and financial organization reached its climax in the second half of the XIXth century

with the gold standard, and the powerful western European nations (England, France, Germany). It is also the peak of the age of modern colonialism, in Africa and the Far East. Students must review the conquest of India by Britain, beginning in the XVIIth century, the split of Africa between England and France, with the near war at Fachoda in 1898, the brutal opening of China in the 1830' and 40's, the Opium wars, and the prying open of Japan

in 1854, the colonial policy of Jules Ferry. Students must also review the emergence of the United States, as well as the more or less failed independences in South America in the early XIXth century,

the Monroe doctrine, the tentative creation of a

Mexican empire in the 1860's by the European catholic powers, etc.

World War I

All this lead to the cataclysm of WWI, which marked the end of an ancient world. In some respects, the entire "extended" XIXth century, from the 1780's until 1914, is a "transition period", from a political and social viewpoint, between

an ancient regime of centralized monarchies, and modern "democracies". The XIXth century is the century of revolutions,

of the rise of "national feelings" (and also the crush of regional

particularisms), of the emergence of industrial proletariat,

and as a consequence of the first social ideas (cf. utopians,

Saint-Simon, etc.), of the first powerful technical achievements of science,

of thermodynamics, electricity and electromagnetism, of the rise of large scale industrial capitalism, and

also of the first large economic depression of an industrial origin

(c1870-c1890).

Attempts to set up international organisations endowed

with powers over nation states

After WWI, the victorious Allies set up the Society of Nations, to harmonize

their diplomatic relations, and tried to come back to the gold standard system. They also imposed "Carthaginian" war reparations on Germany which contributed to the burst of the second world conflict. The 20's and 30's were a period of monetary, financial, economic and political instability, with a second great

world depression. And the world had to go through another world war before being able to

install peace in the West.

Post WWII world, Bretton Woods, the World bank and the

IMF

The modern post WWII world saw the establishment of a new monetary system set up at Bretton Woods,

together with international financial institutions like the world bank and the IMF

and political institutions like the United Nations. In the West it was a Pax Americana. And the world lived under the threat of a third world war between the

West and the communist block.

The demise of the Bretton Woods system. The

conservative revolution

After the demise of the Bretton Woods monetary system, in 1971, the world entered a period of currency instability. It was still dominated by the economic and military power of the United States. Since the eighties, the Thatcher/Reagan revolution

swung the

western world back to societies with less welfare and more tough liberalism. The history of the emergence of

nationally sponsored welfare (retirement pensions, health protection,

unemployment protection, free education, help to housing, to home owning, and,

little by little, to all sorts of things...), beginning with Bismarck at the end of the XIXth century is also a topic students should review in order to get the most from this course

in finance, which purports to shed light, from a financial point of view, on the future of the world.

The financial revolution, the growing US

trade deficit, the subprime crisis, the future...

Finally the last thirty years saw the collapse of the soviet

empire, the fantastic deepening of the United States trade deficit, the growing

disorganization of national finances in many western countries, particularly the

US (the "subprime crisis" is only the latest illustration), the emergence of new world powers (China, India, other

Asian countries),

and also the emergence of internet, which at the same time brings new links between people worldwide,

but also erodes subtly and profoundly the power of national governments. All

this is preparing a future much different from the past - a future where

current nation states are likely to play a lesser role than today.

Original Eurodollars:

It is against this background that appeared, in the 1950's, at the height of the

cold war, some new "unregulated" banking activities. In 1956, after the invasion of Hungary by soviet troops to maintain the communist order in eastern Europe (after Berlin in 1953, and before Prague in 1968), the soviets who had dollars assets held in

American banks were afraid that the United States would freeze these assets, that is block their bank accounts in credit in the US. So they decided to move their dollars, in the form of paper bank notes and electronic transfers, to a British bank they had in London, the Moscow Narodny Bank, and began to do banking in dollars from their

British bank. For instance, "on February 28, 1957, the Moscow Narodny Bank in London put out to loan, through a London merchant bank, the sum of $800 000. This minuscule amount was borrowed and repaid outside the American banking system" (source: Adam Smith (George Goodman), "Paper Money", Dell publishing, 1981).

Dollars used in such banking and financial activities outside the United

States, and outside the reach of American regulatory power, are called

eurodollars (be they in London, Tokyo or Rio Janeiro).

The Moscow Narodny Bank was not yet entirely "off-shore", it was outside the

US banking system, but still paid taxes, in England, on the profits it showed in

its books.

More on the original Eurodollars:

The Russian dollars deposited at the British Moscow Narodny Bank were in the assets of that

British bank, and in its liabilities as a credit to the Russian depositors, as is usual.

These dollar assets were nothing more than dollar bank notes in the vault of the Narodny bank

as well as claims on some American banks somewhere in the United States, that is deposits in American banks, on their liability side again... But the Americans could no longer freeze these dollars, because they belonged to a British bank.

This is the gist of the Russian operation: instead of being creditors to

American banks, they became creditors to a British bank, and the British bank

was a creditor to American banks. Since the US would not freeze the assets of a

British bank, the ultimately Russian assets became outside the reach of the US.

The British bank was responsible for paying, on demand or according to some contract, the Russian deposits.

These Eurodollars were not "new money" in the sense of money created by opening a new loan from scratch on the asset side, like banks regularly do in their national currency, and opening a corresponding credit in dollars on the liability side.

They were equivalent to "liability money"100%-covered by real American dollars in the United States, just like bank notes ("liability money") used to be 100%-covered by gold deposits.

Yet these dollars assets of the British bank were not under the regulatory control of the American authorities. The British bank could do whatever it wanted with them.

Eurodollars or just plain Eurobonds?

Because so far the deposits on the liability side are against 100% deposits on the assets side, and these assets are a currency, and the liabilities are usually remunerated, some authors - like Mishkin - say that Eurodollars are just a variety of Eurobonds. The teacher's opinion is that this view is limitative.

Even less regulated banks:

Genuine tax havens

Some other banks, dealing in big foreign currencies, appeared in authentic

tax havens like the Dutch Indies, Panama, and other places like that, called in

French "paradis fiscaux". These are even less within the reach of authorities of

big western nations.

Off-shore banks do not belong to the organized clearinghouse systems of

banks within a currency zone, controlled by a state

They must deal

on a private basis with other official banks. For instance when a check drawn on

an off-shore bank account is presented to an official American bank, that bank

may or may not accept the check (whereas within a clearinghouse system under normal circumstances it must accept checks drawn on the other banks of the clearinghouse). But

this problem is more theoretical than real for the reason described below.

The clients of off-shore banks

In fact, the main clients of unregulated and off-shore banks are large

industrial firms and large western banks, which find it handy to have some of

their activity carried out outside the reach of their regulatory authorities.

For instance, Air France airplanes used to be owned by a (Air France controlled)

firm in Panama.

Tax havens don't have to be far off-shore

England maintains

fiscal havens in the Anglo-Norman islands, and in the isle of Man.

Liechtenstein is a tax haven (much talked about in February 2008, because

it was "discovered" that many economic leaders, from Germany, France, etc., kept secret accounts there

to shirk taxes).

Without falling into the trap of populist all-sweeping criticisms, one must

admit that "democracy" is more a concept in political science than a reality.

LETS:

There exist other monetary and banking systems,

within a country, which are distinct from the official monetary and banking

system of the society. These are called

Local Exchange Trading Systems (in French, "Systèmes d'échange locaux", or

SEL). They are small spontaneous systems of exchange, within a community, which

use a unit of count akin to a money. They are tolerated by national authorities

as long as they remain small and do not correspond to an important lack of fiscal revenues. Example in summer 2011 in Toulouse.

Financial markets

We saw in lesson 1 what are financial products, also called

financial securities. We recall them briefly here. There are three ways

to pay, in a transaction where we buy goods:

- with other goods: it is called barter

- with money: it is the standard way to pay

- with a promise (of one sort or another) to pay in the

future an amount which has "a value today" equal to the price we would pay if

we were to pay with plain money

We saw the origin of money and of financial securities.

Modern money is actually a variety of financial security (for instance a bank

note entitling to gold, deposited in a bank) which has been transformed into a

legal tender means of payment on its own.

Financial markets are places where financial securities

are traded.

Some of these markets have a physical existence and location:

the various stock markets in the world. Sometimes, on the other hand, we just

refer to "a conceptual market" which is worldwide, where exchanges are carried

out on the phone or via computer links, and with no physical location.

Origin of the French word "la Bourse"

The French word for the stock market, "la Bourse", comes

from the Vander Beurze

house in Bruges. We can find the

explanation of this origin, at the entry "Bourse",

in the

Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert written in the XVIIIth century.

The New York Stock Exchange

Modern stock markets exist since the XVIth century in

Europe

There were already important stock markets in Europe in the

XVIth century, in Amsterdam, London, Antwerp, Bruges, some other hanseatic

cities, and in France, in Paris, Lyons, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Rouen, etc. Roman

historian Titus-Livius (59bc, 17ad) wrote that there was a market place for

merchants to exchange goods, perhaps of a financial nature, in Rome in 493bc.

Places where important merchants met on a regular basis

Stock markets were essentially physical locations, in large

cities, where merchants, bankers, insurers, and commercial agents of all sorts

met at fixed times, on certain days, to do business with each other. Attendance

was so important for everyone that the absence of one usual member was taken as

a sign that he was probably going through business difficulties and perhaps had gone

bankrupt.

Read "L'Argent" by Emile Zola

For a historical, yet still very actual, description of

stock market players, their activities, their mentalities, students are invited

to read the novel by Emile Zola, "L'Argent". It is adapted from an episode of

French financial history: the

krach of

the Union Générale in 1882.

Functions of financial markets:

Financial markets fulfill several functions (adapted from Levinson,

"Guide to Financial Markets", The Economist, 2006)

- Price setting: they enable one to know the market price of something

- Asset valuation: they enable firms, particularly insurance

companies, to know the actual value of their assets

- Arbitrage: if the same goods are for sale at different

prices in different markets (and the transportation costs are insignificant)

markets players will buy where it's low and sell where it's high, thereby

leveling out prices

- Raising capital: firms can find needed capital, not only from banks, but on

financial markets

- Commercial transactions: financial market provide the "grease"

to commerce. A buyer may pay a seller with a bill of exchange, and the

seller may redeem his/her bill for cash, before its due date

- Investing: people with a surplus of cash can invest it in

order to "make it work"

- Risk management: markets offer the possibility to modulate

the risk a player wants to bear or to take on

This last item, risk management, goes back to the earliest of

times. For instance, a farmer (A) can sign, in the Spring of a year, at date t, a contract

with a market player (B), to sell his crop to B in the Fall, at date T, at a

price fixed at date t. The crop and the money will be exchanged at date T, but

the contract is signed at t. Such a contract is called a forward contract.

It enables A to avoid the risk of price fluctuations between t and T, and to be

sure to get a specified amount of money at T. B takes on the risk. We shall meet

many contracts involving in a sophisticated way the transfer of risk.

Size of financial markets:

The yearly issues of new securities is given in table 1.1 (from

Levinson):

|

Table 1.1 Amounts raised in financial markets ($bn, net

of repayments) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1996 |

1998 |

2000 |

2002 |

2004 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Domestic bonds and notes |

1 497 |

1 600 |

865 |

1 672 |

2 461 |

|

International bonds and notes |

499 |

669 |

1 148 |

1 014 |

1 560 |

|

International bank loans |

405 |

115 |

714 |

540 |

1 343 |

|

Domestic money market instruments |

401 |

377 |

377 |

103 |

774 |

|

Domestic equity issues |

438 |

472 |

901 |

320 |

593 |

|

International equity issues |

83 |

125 |

318 |

103 |

214 |

|

International money market instruments |

41 |

10 |

87 |

2 |

61 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total (excluding domestic loans) |

3 364 |

3 368 |

4 410 |

3 754 |

7 006 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources : Bank for International Settlements; World Federation of Exchanges |

|

|

|

Flow view

The total issue of new securities (excluding domestic loans

that were not resold in the form of securities),

in 2004, was $7 trillions. As Levinson says, "estimating the overall size of the

financial markets is difficult. It is hard in the first place to decide exactly

what transactions should be included under the rubric "financial markets", and

there is no way to compile complete data on each of the millions of sales and

purchases occurring each year."

Stock view

Another way to look at the size of markets is to estimate the

financial securities outstanding at the end of each year. Measured with this

"stock approach" (as opposed to the above "flow" approach), the figures from

1996 to 2004 are:

|

Table 1.2 The world's financial markets ($tr) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1996 |

1998 |

2000 |

2002 |

2004 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Domestic equities |

19,6 |

25,4 |

31,1 |

22,8 |

37,2 |

|

Domestic bonds and notes |

21,2 |

23,8 |

23,8 |

27,9 |

35,9 |

|

International bank loans |

8,3 |

8,2 |

8,3 |

10,1 |

13,9 |

|

International bonds and notes |

3,1 |

4,1 |

6,1 |

8,8 |

13,2 |

|

Domestic money market instruments |

4,5 |

5,2 |

6,0 |

6,3 |

8,2 |

|

International money market instruments |

0,2 |

0,2 |

0,3 |

0,4 |

0,7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total value outstanding |

56,9 |

66,9 |

75,6 |

76,3 |

109,1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source : Bank for International Settlements |

|

|

|

|

|

that is a total, in 2004, of $109 trillions. This is two to

three times the world GDP.

The 2007 stock view

figure is estimated at $165 trillions.

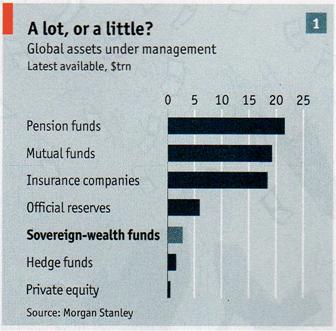

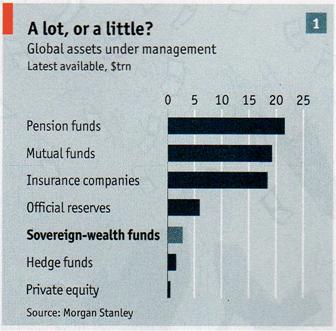

And the major

security holders are given in the table below:

(Source : The Economist, 19 January 2008)

Evolution of financial markets since 1980

The Thatcher / Reagan revolution

Financial markets evolved profoundly and grew rapidly since 1980. This is due

to the political Thatcher/Reagan revolution which lead to a vast

liberalization of various economic sectors, including banking and finance, and to

the technological computer revolution which developed financial markets,

at the expense of banks.

The 3 Ds

The movement, in the early 80's, from traditional banking to

financial markets is described, in French, as "les trois D's" ("the three D's"):

- dérégulation (=deregulation)

- désintermédiation (=disintermediation, i.e. the decrease

of the role of banks as intermediaries between investors and borrowers)

- décloisonnement (=dismantling of barriers between the various

types of financial activities, which used to forbid the same institutions to

do several of them at the same time)

Most practical consequences of the Thatcher / Reagan

revolution

The political Thatcher/Reagan revolution lead more specifically to four factors that spurred the development of financial markets (from Levinson):

- Lower inflation

- Development of pensions funds

- Stock and bond market performance

- Risk management

Lower inflation:

Inflation is a curse on the economy

of a society.

It disorganizes contracts, rents, repayments, revenues. It has existed at various epochs in the past. Among many others, a famous very long episode of inflation is the "Price revolution" between 1500 and 1650, when prices of various commodities and usual products were multiplied by a factor between 5 and 7 in many European countries.

Suspension of the convertibility of the British pound

During the Napoleonic wars, England suspended convertibility of the pound into gold, and suffered from inflation (as is usually the case in war time). A lord named King complained that the revenues from his estates were losing their purchasing power, and asked to be paid directly with fixed amounts of gold, or to be allowed to modify the contracts with his tenants to increase the rents expressed in pounds sterling. The following illustration helps understand the problem:

The problem of Lord King

At time t, you borrowed £100 pounds from a lender: you received £100 in bank notes and gave the lender an IOU of £100. At that date t, £100 could buy 25 oz of gold. Some time later, at time T, you must repay your debt (aside from the interests which you paid too). At this date T, suppose £100 can now buy only 22 oz of gold. Should you refund £100 to your lender or £113,6 so that he could again buy 25 oz of gold?

The Great Price revolution 1500-1650

Concerning the Price revolution, it is still debated whether it is a consequence of the influx of precious metals from the New world, or rather if it has only accelerated it. Some people even think it is one of the causes of the French revolution, because it transferred economic and social power from the aristocracy to the merchant class.

Causes of inflation

The opinion of the teacher is that inflation is the symptom of a fine malfunction of the social fabric (in the sense of a tightly knit system), the consequence of which is price increases. When economic science has made some progress, we may identify and measure more fundamental social parameters, on which governments will be able to act. So far, only "common sense" can guide political action ("responsible monetary policy", "restraint in salary increases", etc.); but it often leads to heated political and social debates as to what is better, a strict monetary policy or a social policy? For instance, in the early 20's in England, Churchill complained that the head of the Bank of England preferred to maintain "a strict monetary policy and enjoy a strong pound sterling" than to "address the problem of the 1 million unemployed people". At times unfortunately common sense can be misguiding. It may also mask social struggles and the protection of private interests beneath the cloak of "competence", "complex problems ordinary people cannot understand", etc. Political leaders, as well as central bankers, are often as befuddled as anyone, but they try not to show it. It makes for fun-to-read biographies and memoirs later on, when some witnesses write about the private political meetings they attended.

One cannot

dissociate financial questions from political and social questions

One of the themes of this course is that one cannot dissociate financial questions from political and social questions. The objective of the course is that students become familiar with the main financial products, their markets, actors, functions, technical aspects, but also with the political and social issues related to them.

Hyperinflations

There were terrific inflations (called hyperinflations) in Weimar Germany in 1923, and in Hungary in 1945. A creeping inflation all along the 50's and 60's became a severe one in the 70's throughout the Western world. At the end of the 70's it reached 13% in the US, and close to 20% in France.

Hungarian hyperinflation

Paul Volcker "broke the back" of inflation

In 1980, Paul Volcker, then head of the US Federal reserve, decided to let short term interest rates go very high with the aim of breaking inflation. Here is a picture of the interest rates in the United State over the last two centuries (it's actually the ten year bonds, but short term rates display a similar curve):

Volcker was successful in breaking inflation in the US. Then, with a slight delay, inflation subsided all over the Western world. But if you think of it, this curve of the interest rates over two centuries shows that something

tremendous happened in the late XXth century, in the developed world, in financial and monetary terms.

Value of gold in France since 1800

An idea of French inflation is given by the following table

of devaluations of the French Franc since Napoleon's "franc

Germinal":

|

French devaluations from 1803 to 1969 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Franc |

|

mg of gold 9/10th purity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. |

1803 |

|

Germinal |

|

322,58 |

|

|

2. |

1928 |

|

Poincaré |

|

65,50 |

|

|

3. |

1936 |

|

Auriol |

|

49,00 |

|

|

4. |

1937 |

|

Bonnet |

|

43,00 |

|

|

5. |

1939 |

|

Reynaud |

|

23,34 |

|

|

6. |

1945 |

|

Pleven |

|

7,60 |

|

|

7. |

1948 |

|

Meyer |

|

4,14 |

|

|

8. |

1949 |

|

Petsche |

|

2,54 |

|

|

9. |

1958 |

|

Pinay |

|

1,80 |

|

|

10. |

1969 |

|

Pompidou |

("old franc") |

1,60 |

|

Source: Guitton & Bramoullé, "La Monnaie", Dalloz, 6th edition,

1987 (p. 523)

After, 1971, the French Franc "floated" against other

currencies, and was no longer directly of indirectly pegged to gold. There were

further official devaluations, particularly at the beginning of the first

Mitterrand mandate, until the switch to the euro in 1999/2002.

The above table is different from a classical "series of

deflators" (which gives the yearly evolution of the nominal quantity of money

needed to buy a stable basket of goods and services). But it is very talkative

too: it shows how much gold one French Franc bought over time.

Inflation and fever:

There are situations like the beginning of 2008, where inflation is not the consequence of an increased money supply. In early 2008, in France, inflation is officially around 3.8% on a yearly basis, but if one concentrates on consumer products bought regularly (food and consumable household products, excluding things like flat TV screens or cellular phones) it looks more like 10% to 20%. Then what is the cause? One (soft) theory says "it is a consequence of the great debt imbalances in society, in particular the huge government debt"; inflation plays the same role as fever in a body attacked by microbes. Inflation is some sort of homeostatic regulation which will wipe out a good part of the debt, since from sheer arithmetic it will become a smaller proportion of the GDP (if everything costs twice as much, a fixed debt is automatically divided by two in constant monetary unit).

Isn't a small inflation good?

Notice that a "reasonably small" amount of inflation, like 1% or 2% a year, of the official money used for payments, is not necessarily a bad thing. It forces people to spend their earnings, either investing them or consuming them, at any rate making them participate in the economy. It is similar to an idea, a priori strange, proposed by Silvio Gesell about a century ago: that of "melting money". The long inflation of the "Price revolution" between 1500 and 1650, of 1,3% a year on average, brought about a new world order arguably better than the previous one.

Pensions funds:

The 80's and 90's are also the decades of unraveling some of the achievements of the welfare state (retirement money, health coverage, free education, help to home acquisition, broad public services, etc.).

In particular, the retirement schemes put in place since WWII began to show signs of imminent collapse (within a generation or two), due to a demography with less young people to support old ones.

There are basically two economic schemes to organize the payment of retirement money to old people:

- redistribution from young people working to old people retired

- capitalization by people while they are working, in order to live off the income from their capital when they are old

The first system, which is akin to a tax (the charges paid by workers and their employers to the state, on top of the salary they receive), is viewed as more social, more solidarity oriented.

The other system is simpler: you save money regularly during your working life, and then you live off the income from your capital.

In fact, the two systems are less different than they seem.

First of all,

there are intermediate schemes between pure individual capitalization, and

retirement money managed by the state. In the US many retirements funds are

managed by firms. For example, in the automotive industry, the three large car

manufacturers have their own funds, into which auto workers pour money all their

working life long. And then the funds take charge of their retirement. It is

like some sort of insurance. But the car industry funds in the US will not be

able to pay all the retirement money to their workers that they forecast to have

to pay. It is in part because the retirement funds were badly invested into

risky portfolios. So now they turn to the American government to do something

and it is a big social problem there. A similar problem exists in France, but in

France retirement money comes mostly from a purely redistributive system.

A more profound reason for their similarity

There is a second, more profound, reason why the two systems are less different than they appear to be: capitalization is just a financial scheme to save wealth. When an old person eats some rice, that rice has been grown and packaged by younger people at work. It does not come from "rice saved 40 ago". In other word, the old person may have the monetary means to buy this rice, thanks to his/her personal savings during all her life, as opposed to a redistribution scheme, but in the end it is still young people who support the old ones (as it should be).

Durable tangible goods

The only tangible wealth that can actually be saved over a generation is houses and land

(if we consider stocks as not tangible, and closer to money). A society where people save in a

capitalization scheme for their retirement, putting their wealth into tangible and durable assets, is a society where houses,

apartments, and land, are owned by old wealthy people and rented to younger ones.

Capitalization schemes

So, because of the slow collapse or dismantling of retirement redistribution schemes (and the fact that a redistribution scheme works well when 4 workers support 1 retired person, but not when 2 workers support 1 retired person), many new savers have turned to

capitalization schemes, which in turn spurred the development of pension funds buying financial securities.

Why more purchase of financial securities

You may wonder how come this makes for new purchases of financial securities. Don't the savings in a redistribution

system go into financial securities too? Well, when retirement payments by workers, for the future, are

essentially a tax, the state doesn't need to put this money into financial securities. It can do whatever it likes with it, invest it into infrastructures, or into anything creating society-wide wealth - aside from paying some to older people. But, as we know, not all Western governments have shown financial

responsibility (the more responsible are Scandinavian countries, Canada, and to a lesser extent Britain; the less responsible are France, the United States, Italy, etc.)

In the United States, the biggest pension fund is Calpers. When funds become very big, they begin to have a social and political power which some

people object to as too big.

Stock and bonds performance:

The 80's and 90's (until the burst of the high-tech bubble) were a period of stock market buoyancy, which spurred the development of financial products and markets.

Risk management:

New sophisticated financial products, in the field of "derivatives", enabled investors as well as borrowers to calibrate exactly the risks they were willing to take in various economic deals. This helped the development of the corresponding financial markets.

Evolution of the French balance of payment financial

part

Another illustration of the important development of financial markets worldwide since 1980, is that the item "portfolio

investments" in the French balance of payment was multiplied one hundred fold between 1980 and today.

Main actors

Individual investors, perusing financial newspapers and magazines, and selecting carefully their portfolio of stocks, bonds and other products, are an image of the past. Nowadays the main actors on financial markets are institutional investors:

- pension funds (seen above): they funnel and invest the savings of millions of people, and guarantee them some benefits when they retire. "Typically, pension funds are sponsored by an employer, a group of employers or a labour union. Unlike individual pension accounts, pension funds do not give individuals control over how their savings are invested [...] Pension funds assets are above $20 trillion worldwide. Three countries, the United States, the UK and Japan, account for the overwhelming majority of this amount." (Levinson)

- mutual funds: they are investment firms which combine the investments of many individual investors, and can benefit from a scale effect and make more competent investments. Some funds accept an unlimited number of investors. Some are "closed-end funds".

- hedge funds: there is no precise definition of a hedge fund. The idea is that they are limited to rich investors, take much more risks that standard mutual funds, and have very aggressive investment strategies. The word "hedge" comes from the fact that sometimes these funds use the technique of "hedging" to try and limit the risks they take.

- insurance companies

- etc.

Foreign exchange markets

Foreign exchange markets are the markets where buyers and sellers exchange currencies and related financial products. These markets do not have a well defined physical location; they are mostly

worldwide; trading is done via telecommunication systems; and we could as well

speak of one foreign exchange market, but the custom is to use the plural.

Types of markets:

There are two main markets, the spot market and the future market.

- spot market: the transactions happen and are completed

immediately, at the date we customarily call t. When you buy Mexican pesos

with dollars on the spot market, you usually go to the window of a bank, give out your dollars and receive pesos at a certain exchange rate, called the spot exchange rate. Technically certain larger transactions may be completed within two working days and are still called spot.

- future market: at time t, the two parties sign a contract to exchange, later on, at time T (for example, if t is in February, T is the first of July) currencies at an exchange rate set at t. This exchange rate is called the 1st of July forward exchange rate,

as of February (this forward rate will evolve everyday until the 1st of July). For example, an American manufacturer sold machinery to a Swiss client and expects to receive SFr10 million sometimes before the 1st of July. He may buy a futures contract on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. This will prevent him from the risk of fluctuation of the rate dollar/SFr in the mean time.

There are two more markets related to the future market: the options market (which is relatively small), and the derivatives market (which comprises all complex contracts involving time, and which are not just futures).

Derivative market:

- forward contracts: agreements similar to futures contracts, but negotiated on a purely private basis between a buyer and a seller,

whereas future contracts are "calibrated contracts" handled by a stock exchange. (Remember, a stock exchange is a firm that organizes a stock market. It is, as the saying goes, the buyer of all sellers, and the seller of all buyers. It provides information, and various securities.)

- foreign-exchange swap: an exchange on one date t, and the offsetting reverse exchange on another date T,

all agreed upon at signing time. Swaps accounted for about 56% of all foreign exchange trading in 2004 (Levinson)

- forward rate agreements

- barrier options

- etc.

The players:

Foreign exchange markets are useful to a variety of players:

- exporters and importers: they need foreign currencies for

their commercial operations

- investors: they try to invest their savings into currencies

that will provide high yield (and/or high capital gains)

- speculators: they gamble on probable evolution of exchange

rates (see Soros below)

- governments: they buy or sell foreign currency reserves in

order to try and control the exchange rate of their national currency (see

Asian crisis below)

Even though there is no precise physical location, London and New York are the main financial places for foreign exchange.

|

Table 2.1 Geographic distribution of traditional

currency tradinga |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

April 1989 |

|

April 1998 |

|

April 2004 |

|

|

Average |

|

|

Average |

|

|

Average |

|

|

|

daily |

Market |

|

daily |

Market |

|

daily |

Market |

|

|

turnover |

share |

|

turnover |

share |

|

turnover |

share |

|

|

($ billions) |

(%) |

|

($ billions) |

(%) |

|

($ billions) |

(%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UK |

184,0 |

26 |

|

637,3 |

32 |

|

753 |

31,3 |

|

US |

115,2 |

16 |

|

350,9 |

18 |

|

461 |

19,2 |

|

Japan |

110,8 |

15 |

|

148,6 |

8 |

|

199 |

8,3 |

|

Singapore |

55,0 |

8 |

|

139,0 |

7 |

|

125 |

5,2 |

|

Germany |

n/a |

n/a |

|

94,3 |

5 |

|

118 |

4,9 |

|

Hong Kong |

48,8 |

7 |

|

78,6 |

4 |

|

102 |

4,2 |

|

Australia |

28,9 |

4 |

|

46,6 |

2 |

|

81 |

3,4 |

|

Switzerland |

56,0 |

8 |

|

81,7 |

4 |

|

79 |

3,3 |

|

France |

23,2 |

3 |

|

71,9 |

4 |

|

63 |

2,6 |

|

Canada |

15,0 |

2 |

|

37,0 |

2 |

|

54 |

2,2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a Traditional products include spot transactions, forwards and

foreign-exchange swaps. |

|

|

Source : Bank for International Settlements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

For exchange-rate futures contracts, the three main market places worldwide are the Bolsa de Mercadorias & Futuros, in São Paulo, Brazil, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, both in the United States.

Herstatt risk: for large transactions involving two continents, since the two legs of the transaction may not be completed exactly simultaneously, there is a risk that A has shipped to B, and before B has shipped to A, B or B's bank go bankrupt. This is what happened in a famous large transaction in 1974 to the Herstatt bank in Cologne, Germany. So this risk is called the Herstatt risk.

What drives exchange rates?

Many factors drive exchange rates, but ultimately it is the relative attractiveness of one currency compared to the other.

In other words the law of supply and demand applies rather well in foreign-exchange markets.

And in the end, the "attractiveness" of a currency is the expectation to earn or

preserve value in that currency compared to another. This is why comparative

short term interest rates, paid by governments, play a fundamental role in driving exchange rates.

Euro

versus dollar

Since 2001, due to the growing weakness

of the dollar and its foreseeable further loss of value,

the euro gains steadily with respect to the dollar and is now

breaking regularly its record value. The exchange rate in late February 2008 is

1 euro ≈ $1,50. It is likely to see the euro be worth more than $2 within the

next few years.

Here is a graph of the evolution in percentage change:

(source: https://www.ipathetn.com)

Playing with currency rates. Examples:

Covered interest arbitrage

One arbitrage possibility to earn money on exchange markets is called the "covered interest arbitrage". It links spot rates, forward rates, and risk free interest rates in both countries. This is explained with the following illustration:

You are in the UK and have £100 to spare for one year. You want to "make it work" safely. A possibility is to invest your £100 in one year risk free British government bonds. Suppose they pay 5% (and suppose for simplicity there is no inflation in the UK, nor in the US). Another possibility is to exchange your £100 for dollars on the spot market and invest your dollars, and, in one year, do the reverse exchange. In some circumstances this may be advantageous.

If the spot exchange rate is £1 = $1,60, and the dollar bonds yield 7%, and you can change your dollars back into pounds, in one year, at the rate £1 = $1,61 (rate locked today, that is, this is the one year forward exchange rate), then you can get $160 dollars, have them produce $171,20, and arrange today for the exchange back, in one year, to get $171,20/1,61 = £106,34.

In this case, the arbitrage is profitable (and risk less, as an arbitrage, by definition, must be). Since the computers of all professionals in exchange markets worldwide scan permanently all markets for such arbitrage possibilities, it won't last more than a few minutes. The law of supply and demand will drive the spot price of dollars up, and the forward price of pounds up too. For instance, after a little while, the pound may only buy, on the spot market, $1,59. And the forward rate may climb to £1 = $1,62. Then, the same calculations as above show that the operation is not longer profitable.

Carry trade

A practice along the same line as this example bears the name of

"carry trade"

and is carried out on a regular basis by some operators: certain currencies are

attractive as ways to park excess wealth into reserves, and also to speculate.

For instance, for the last ten years, the Japanese yen has been very cheap in

the sense that the interest rates to borrow yens are very low .

"Carry trade" between yens

and other currencies consists in borrowing Japanese yens, changing them into a currency yielding a high interest rate,

earning money that way, then changing back part of the money into yens and refunding the lenders.

It illustrates the limits of simple models to explain movements in exchange

rates.

|

Table 2.5 Typical newspaper currency prices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Country |

Exchange rate |

|

Currency for one dollar |

|

|

|

(dollar equivalent) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tuesday |

|

Monday |

|

Tuesday |

|

Monday |

|

Argentina (peso) |

0,5263 |

|

0,5263 |

|

1,9000 |

|

1,9000 |

|

Australia (dollar) |

0,5195 |

|

0,5152 |

|

1,9249 |

|

1,9410 |

|

Bahrain (dinar) |

2,6525 |

|

2,6532 |

|

0,3770 |

|

0,3769 |

|

Brazil (real) |

0,4227 |

|

0,4227 |

|

2,3655 |

|

2,3650 |

|

Canada (dollar) |

0,6215 |

|

0,6203 |

|

1,6090 |

|

1,6121 |

|

|

1-month forward |

0,6219 |

|

0,6209 |

|

1,6079 |

|

1,6105 |

|

|

3-months forward |

0,6217 |

|

0,6207 |

|

1,6084 |

|

1,6112 |

|

|

6-months forward |

0,6217 |

|

0,6206 |

|

1,6084 |

|

1,6113 |

|

Chili (peso) |

0,001491 |

|

0,001494 |

|

670,55 |

|

669,15 |

|

R.-U. (pound sterling) |

1,4288 |

|

1,4373 |

|

0,6999 |

|

0,6957 |

|

|

1-month forward |

1,4256 |

|

1,4352 |

|

0,7015 |

|

0,6968 |

|

|

3-months forward |

1,4205 |

|

1,4299 |

|

0,7040 |

|

0,6993 |

|

|

6-months forward |

1,4201 |

|

1,4278 |

|

0,7043 |

|

0,7010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Speculation

on the pound in 1992

Fixed change monetary systems, linking in a rigid way the currencies of several countries, like the gold standard (1870-1914), the Bretton Woods system (1944-1971), or the European Monetary System created in 1979, are fragile and can be very costly to maintain, when one central bank must

buy large volumes of its own currency to defend its value with

respect to other currencies. To do so it

uses foreign currency reserves,

special drawing rights at the IMF, or gold. The

attack on

the British pound of September 1992 is an illustration.

After the German reunification in October 1990, the Bundesbank was under

inflationary pressures. To combat inflation, it raised

its leading interest rate from 3% to 10%.

This made investing in the German

Deutsche

Mark very attractive.

In order to maintain a fixed exchange rate of £1 = 2,778 DM,

British monetary authorities were forced to buy a lot of pounds sterling from

speculators selling them. They also raised their base interest rate from 10% to

15%.

Britain could not maintain such a monetary policy and such

purchases for a long time. A devaluation of the pound sterling became

unavoidable. Speculators had anticipated that, and even sold pounds short. To

sell short today, called date t, is a contract where you promise to

sell at a future date T, at a value fixed at t, because you anticipate a spot price then lower than the selling price agreed upon today.

If you turn out to be right, you make a large profit, because you can deliver

at T, at

the agreed price, the goods which you can buy,

on the spot market at T, at a lower price.

The fund of George Soros speculated in such a way on the

likely devaluation of the pound sterling. In the end, it was right. The British

pound was devaluated by 10%. And Soros fund made a profit of $1 billion.

Asian crisis of 1997-1998

It is a "financial and monetary crisis" which started in

Thailand in the Summer of 1997. Let's understand what is meant by a "financial

and monetary crisis", and, to start with, how it began.

In the last quarter of the XXth century, most worldwide FDI (foreign

direct investments) of rich countries, that were not reinvested in rich

countries, were invested in Asia. Thailand, in particular, received a lot of

capital inflows to finance various industrial, commercial and real estate

projects. To stay simple and clear, these capital inflows were foreign

dollars buying Thai bahts, and being then invested into Thai projects, owned,

therefore, by foreigners. In order to be paid, the foreign owners needed

that their investments produce hard currencies (dollars, as opposed to bahts) to be

able to receive dividends. Or indirectly,

anyway, Thailand had to export to receive

dollars in order to pay dividends on FDI's.

Remember what is a balance of payment. Here is France's BOP

in 2004:

The luxury real estate projects around Bangkok did not

perform as expected: many apartments remained empty; rich foreigners did not

buy them for vacation (which would be akin to tourism export).

Thailand did not export as much as

it needed, considering all the FDI it had received. Their payments required

dollars, so Thailand bought dollars with bahts in order to make the required

payments.

More generally "capital fled the country", which means that

owners of Thai projects began to sell them, in exchange for Thai baht, and tried

to exchange their bahts for dollars.

The baht was therefore under pressure. In July 1997, Bangkok

government could no longer maintain the parity of the baht with the dollar. It

was forced to devalue.

Exchange rate: Baht per U.S. Dollar:

Many foreign investments, denominated in bahts or convertible

rapidly only into bahts, instantly lost

value. Then the crisis propagated to several other South-East Asian countries.

And then to Russia and South-America. The Russian crisis was aggravated by

excessive positions in Russian bonds taken by the hedge fund

LTCM.

A financial and monetary crisis, in any given country, is

always a brutal loss of value of investments denominated in the currency of the

country, the consequence of which is a flight of capital away from the country

(local currency being sold by various agents to get hard currencies). The

national currency is eventually devalued, many investors (national and foreign)

lose wealth, and the country is temporarily pushed aside from world economy.