Advanced financeLesson 4: Bond markets

Enterprise, borrowing, finance, time and risk Financing a physical investment Three agents

Why not sell directly to A the financial contract? Separating risky and non risky operations

Comments:

The above picture and explanations do not specify explicitly whether the investor invests in equity or in debt. We already know, from our introductory course in finance, the difference:

In this course we shall use the concept of money in its conventional sense: means of payment, of an official nature, which extinguish debts. Then the study of the exchange of money now, for streams of money in the future, under various conditions, will be reasonably straightforward. But we begin to see that money is some sort of nonquantitative concept (it is a more complex factor, measuring the state of a social system, than conventional wisdom perceives) which sets or does not set the economy in movement. (It has been compared, in turn, to grease, to temperature, to entropy, but all these miss the point: a new description is called for.) It is a paradox that the creators of money can use it right away for consumption and yet it is useful because it sets the economy moving. This was for example a privilege of the Spanish empire during the XVIth century, but for a complex set of reasons it did not profit Spain. It is the privilege of any official issuer of money (it bears the name of seigneurage). It is also the gist of the debate on America's "exorbitant privilege" to print dollars (or T-bills) to pay for its consumption. Modern banks do create money but it is with the double mechanism of receiving a loan and opening a credit, which must be refunded, and this money is not just consumed. So we shall keep in mind that the relationship between the entrepreneur E and the investor I (i.e. the right half of the above picture) embodies deeper phenomena than is immediately apparent in the lending/borrowing of money. The study of equity markets will be the subject of a later lesson. The present present one is debt markets, and, more specifically, the simplest and most important of them: the bond markets.

Earning money In a society, an individual who does not live in autarky has two ways of earning money:

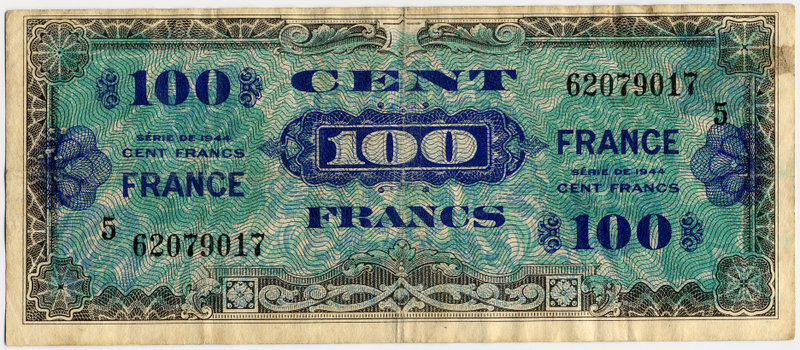

To sell one's work, there are again two possibilities: either work in a firm owned and run by other people, it is the situation of most salaried people; or create a firm and work in it, this is the situation of the above entrepreneur E. Entrepreneur E starts a firm by acquiring initial assets necessary for operations. And, if he doesn't have the necessary initial funds, we saw that he can borrow them (with ou without collateral guarantees), and pay them later, according to a schedule, with the earnings of his firm. If on top of this his firm makes good money, he can pay himself a salary, that is, sell his work to his own firm. As we know, in France, revenues from labor are highly taxed (yet the nation's income statement is in deep deficit, of the order of 100 billion euros a year), and our entrepreneur's only real perspective of getting rich is that his firm become very successful and at some point he sell it to other people. The real economy being full of paradoxes, it is sometimes possible to start the equivalent of a firm which will be able to repay the initial loan and turn a profit, without the entrepreneur doing anything! This is the case when someone E buys an appartment A, say in the Bastille district of Paris, finances 100% of it with a mortgage loan from I, and then rents it to tenants. We have known many situations where the rent covered the repayment of the loan (interest and capital), and after 10 or 15 years, the "entrepreneur" became the full owner of a flat without having put any work in the venture. In certain circumtances, a Leverage Buy Out (LBO) is not much different. A special holding firm H is set up, financed mostly by debt (i.e. with a "high leverage"). The cash raised is then used to buy an existing firm F (often a subsidiary which a group wants to divest). Finally the existing firm F is somewhat reorganised, "turned around" to produce high cash flows, and these are used to pay quickly back the debt of the holding H. In several countries, tax laws facilitate LBO's by taxing lightly the dividends funneled from F to H. The second way to earn money is to profit, we said, from a variation in the value of assets. A simple illustrative example of a pure speculation is given by the father of an acquaintance of mine, who, at the end of WWII, bought all the stamps and bank notes that AMGOT had planned to introduce in France, but that De Gaulle refused, and which turned out to be useless. In fact they turned out to become "collectors items". My friend's father was careful not to resell them too quickly. Over the course of two decades, he made a fortune, and his son enjoys a large wealth that leaves him time to do high level mathematics (a notoriously inadequate activity to become rich).

Of course, when one is able to control the variation in value of the acquired assets, like buying farm land, and then buying municipal agents to reclassify it as constructible land, it is all the better, although it is discouraged in courses in business ethics. (Whether courses in business ethics are of any use is questionable, but it employs people.) These are final introductory comments on money and value before we turn to the mechanisms of bonds.

Bonds are nothing more than plain loans split among many lenders. They appeared in the XIIth century when some princes found that their bankers were reluctant to (or just could not) lend them more than a certain sum. By splitting the money needed among several investors, the borrower could raise more money, while each investor limited its exposure. The first recorded bond was issued in Venice in 1157 and served to finance a war with Constantinople (Levinson, p 58). The simplest bond, also called "plain vanilla" bond, has the following structure (we take the example of a 7 year 5% bond):

the arrow pointing downward represent money from investor to issuer, and the arrows pointing upward represent money from the issuer to the bond holder.

Bonds used to be thought of as dull financial products, good for safe investments to keep wealth for the next generation. But since the 1980's this has changed. We shall see in a moment the large variety of bonds, beyond the plain vanilla bond described above, and aside from all the so-called "exotic", "derivative" or "structured" financial products.

Size of markets Giving a numerical figure to measure the bond markets (or market) is difficult. For one thing, contrary to stocks which are all handled through stock markets and are reasonably easy to monitor, most bonds are issued and traded over-the-counter (in French, "de gré à gré"), that is in a private transaction between an issuer and an investor. It is not mandatory that an official authority record the bond. An estimated figure, however, is that the total size of the bond market worldwide (the outstanding bonds) at the end of 2004 was approximately $50 trillion, of which roughly $37 trillion traded on domestic markets, and another $13 trillion traded outside the issuer's country of residence. In the United States, the largest single market, over $400 billion worth of bonds change hands on an average day, and the value of outstanding bonds at March 2005 exceeded $13 trillion (Levinson).

Why issue bonds?

This last point simply says "if you don't have the money, you may borrow it". Beyond its mundane looking appearance, it actually touches on the deep nature of money and credit. In a certain modelling approach, money and credit are the same: if you don't have money, but have credit (i.e. people are willing to lend you money), "for all practical purposes" it is as if you had money. And conversely, to have money is useless if you can neither consume it nor lend it to somebody else whom you trust. For example, landing on a desert island with a trunk full of euro bills, or even gold, is useless.

Who issues bonds? Four basic types of entities issue bonds (from Levinson). National governments Bonds backed by the full faith and credit of national governments are called sovereigns. These are generally considered the most secure type of bond. A national government has strong incentives to pay on time in order to retain access to credit markets, and it has extraordinary powers, including the ability to print money and to take control of foreign- currency reserves, that can be employed to make payments. Notice that, for a government, printing savings bonds or printing money are not that much different. US debt to foreign countries in the form of US treasury bonds

The best-known sovereigns are those issued by the governments of large, wealthy countries. US Treasury bonds, known as Treasuries, are the most widely held securities in the world, with $5.3 trillion in private ownership as of early March 2008 (the above table shows the part owned by foreign countries). Other popular sovereigns include Japanese government bonds, called JGBs; the German government's Bundesanleihen, or Bunds; the gilt-edged shares issued by the British government, known as gilts', and OATs, the French government's Obligations assimilables du trésor. Governments of so-called emerging economies, such as Brazil, Argentina and Russia, also issue large amounts of bonds. Another category of sovereigns includes bonds issued by entities, such as a province or an enterprise, for which a national government has agreed to take responsibility. Investors' enthusiasm for such bonds will depend, among other things, on whether the government has made a legally binding commitment to repay or has only an unenforceable moral obligation. In many countries the amount of debt for which the national government is potentially responsible is extremely high. In the United States, for example, federally sponsored agencies had $2.7 trillion in bonds outstanding as of 2005. Although much of this does not represent legal obligations of the US government, the government would come under heavy pressure to pay if one of the issuing agencies were to default. Lower levels government Bonds issued by a government at the subnational level, such as a city, a province or a state, are called semi-sovereigns. Semi-sovereigns are generally riskier than sovereigns because a city, unlike a national government, has no power to print money or to take control of foreign exchange. The best-known semi-sovereigns are the municipal bonds issued by state and local governments in the United States, which are favoured by some investors because the interest is exempt from US federal income taxes and income taxes in the issuer's state. About $2.1 trillion worth were outstanding in 2005. Canadian provincial bonds, Italian local government bonds and the bonds of Japanese regions and municipalities are also widely traded. Many countries, however, deliberately seek to keep sub- sovereign entities away from the bond markets. This serves to limit their indebtedness, but also has the less noble goal of providing a steady flow of loan business to balks. Germany's states, or Länder, have emerged as significant issuers, with €170 billion of bonds outstanding at the end of 2004 - a leap from only €59 billion of bond indebtedness in 1999. German local governments, however, had almost no bonds outstanding. There are many categories of semi-sovereigns, depending on the way in which repayment is assured. A general-obligation bond gives the bondholder a priority claim on the issuer's tax revenue in the event of default. A revenue bond finances a particular project and gives bondholders a claim only on the revenue the project generates; in the case of a revenue bond issued to build a municipal car park, for example, bondholders cannot rely on the city government to make payments if the car park fails to generate sufficient revenue. Special-purpose bonds provide for repayment from a particular revenue source, such as a tax on hotel stays dedicated to service the bonds for a convention centre, but usually are not backed by the issuer's general fund. Public-sector debt, including sovereign and semi-sovereign issues, accounts for about 60% of all domestic debt worldwide. The total amount of public-sector debt outstanding at June 2005 was almost $24 trillion, of which $22 trillion was issued by governments within their domestic bond markets and $1.4 trillion was issued internationally. Corporations Corporate bonds are issued by a business enterprise, whether owned by private investors or by a government. Large firms may have many debt issues outstanding at a given time. In issuing a secured obligation, the firm must pledge specific assets to bondholders. In the case of an electric utility that sells secured bonds to finance a generating plant, for example, the bondholders might be entitled to take possession of and sell the plant if the company defaults on its bonds, but they would have no claim on other generating plants or the revenue they earn. The holders of general-purpose debt have first claim on the company's revenue and assets if the firm defaults, save those pledged to secured bondholders. The holders of subordinated debt have no claim on assets or income until all other bondholders have been paid. A big firm may have several classes of subordinated debt. Mezzanine debt is a bond issue that has less security than the issuer's other bonds, but more than its shares. Securitization vehicles An asset-backed security is a type of bond on which the required payments will be made out of the income generated by specific assets, such as mortgage loans or future sales. Some asset-backed securities are initiated by government agencies, others by private-sector entities. These sorts of securities are assembled by an investment bank, and often do not represent the obligations of a particular issuer. (Asset-backed securities are discussed in the next lesson.)

Illustration of the securitization process: Fannie Mae lends money in exchange for mortgage-loans (right part of the picture), and then "securitizes" them into a new bond (left part of the picture) the payments of which are not guaranteed by Fannie Mae, but rest only on the payments from the home owners. (Technically Fannie Mae does not deal directly, on the right, with home owners, but with local institutions lending to home owners.)

The distinctions among the various categories of bonds are often blurred. Government agencies, for example, frequently issue bonds to assist private companies, although investors may have no legal claim against the government if the issuer fails to pay. National governments may lend their moral support, but not necessarily their full faith and credit, to bond issues by state-owned enterprises or even by private enterprises. Corporations in one country may arrange for bonds to be issued by subsidiaries in other countries, eliminating the parent's liability in the event of default but making payment dependent upon the policies of the foreign government.

National markets

Read Levinson (chapter 4) on: Issuing bonds

No more coupons The changing nature of the market

A bond is a financial contract between an investor (lending money) and an issuer of bond (borrowing money) specifying how the issuer will remunerate and pay back the investor. All sorts of refinements can be imagined. Before the 1980's, as we saw, bonds were mostly simple mundane products, and were usually kept by their intial buyer on the primary market. Since then things have changed. Many variations on the basic contract have been introduced. When the financial contract stays within certain limits of sophistication, we are still in the realm of bonds; while if the level of sophistication of the contract becomes high (with payments, for instance, depending upon the happenstance of certain future events) we enter the realm of structured financial products, exotic products and derivatives. Here is a list of financial products still qualifying as bonds:

Bonds that have options attached to them are called structured securities. Technically, callables, putables and convertibles are simple examples of structured securities.

We review briefly, below, the basic properties of bonds. For an more complete elementary discussion, students may go to the teacher's first year course in accounting and finance. When studying bonds, one must distinguish clearly between the primary market and the secondary market. On the primary market, bonds are new financial products issued by borrowers (also called issuers, or sellers). The money paid by their buyer (also called investor, lender, or bondholder) goes into the pocket of the issuer, usually to finance a physical project. On the secondary market, bonds are financial products issued some times ago and which are traded between two bondholders. The money going from the buyer to the seller does not end up in the till of the initial issuer. The price at which the bond is sold and bought on the secondary market does not have to be and is usually not its face value. To review the properties of bonds, let's concentrate once again on a 7 year 5% "plain vanilla" bond of face value 1000 euros. Maturity: the term is used alternatively for the date at which the bond will be paid back, and for the number of years to go until that date.

Interest rate: it is the yearly payment from the issuer to the buyer until maturity, expressed as a percentage of face value. It is also called the coupon rate, because when bonds were paper securities, they had coupons which the holder would have to tear off and take to the bank managing the bond for the issuer. The coupon would then be exchanged for the interest payment. There are plenty of variations on this simple structure. Some bonds have quarterly payments or semi-annual payments. Some bonds are "to the bearer" (whoever holds them is their owner) and other bonds have a "registered buyer" (their buyer is recorded in the books of the bank managing the bond for the issuer). Buying a bond is an investment with all the standard characteristics of any other investment. Remember that for any investment (physical of financial) there are two fundamental rates:

The opportunity cost of capital of an investment is used to compute the present values of the future cash flows and therefore its NPV. For a new bond, the opportunity cost of capital and the IRR are equal, and they are both equal to the coupon rate. For the IRR it is a simple algebraic calculation to check this. For the opportunity cost of capital, it requires a full-fledged model of the randomness of securities under study, which we shall not get into. Suffices to say that the randomness of the future cash flows, for the investor, comes from the risk that seller defaults on some of its payments. In the case of a "sure borrower" (the government of a large prosperous nation), there is still randomness related to future purchasing power of the issuer currency: that is the risk of future inflation in the issuer country or of future exchange rate decline between the currency in which the bond is denominated and other currencies. For instance, this is exactly what's happening to foreign holders of US bonds: over the past few years, as of 2008, the dollar has lost ground compared to the euro, the yen, and to a lesser extent the yuan. And this trend seems likely to continue. (Technical note: for bonds the framework of discounting is somewhat different from that for shares, because we use the "max cash flows" and not the "expected cash flows" that would take into account the default risk each year. But this point can be technically cleared, and the two methods are equivalent to compute the new price of old bonds see below calculation of prices of old bonds.) So, for an investment into a new bond, like for any financial investment, NPV = 0. We shall see in a minute that this is also true of old bonds and that it is precisely how one computes the price of an old bond.

On the secondary market, for an old bond we define several concepts. Current yield: it is the annual coupon divided by the current price. For instance, if after two years, the current price today of the above bond is 1065 euros, its current yield will be 50/1065 = 4,69%. This yield does not bear much significance.

Yield to maturity: (this one is not new, but is important) it is the IRR of the investment into the second hand bond. Let's consider the 7 year 5% bond which is traded after two years:

There are now 5 years to go, and, for the investor, the stream of cash flows during these five years is [-price today, 50, 50, 50, 50, 1050]. If the price today is 1065€, then we can compute the IRR for the investor: it is, as you remember, the value of the discounting factor r such that NPV = 0. The general equation to solve for the unknown r is: General discounting formula : NPV(Investment, r) = -price today + C1/(1+r) + C2/(1+r)2 + ... + Cn-1/(1+r)n-1 + Cn/(1+r)n = 0

The calculations using Excel, first of all using a discounting factor of 10%, give this (you may make a note of the formula to compute the present value of each future cash flow):

And then, with the "goal seek" tool of Excel,

we obtain IRR = 3,56% This "yield to maturity" of 3,56% is a more significant financial figure than the current yield computed above.

Duration: practitioners in the bond market use the concept of duration of a bond. We quote Levinson: "It is a number expressing how quickly the investor will receive half of the total payment due over the bond's remaining life, with an adjustment for the fact that payments in the distant future are worth less than payments due soon. This complicated concept can be grasped by looking at two extremes. A zero-coupon bond offers payments only at maturity, so its duration is precisely equal to its term. A hypothetical ten-year bond yielding, say, 70% annually lets the owner collect a great deal of money in the early years of ownership, so its duration is much shorter than its term. Most bonds fall in between. If two bonds have identical terms, the one with the higher yield will have the shorter duration, because the holder is receiving more money sooner." The concept of duration does not add any substance to the general concepts of discounting future cash flows, NPV and IRR, but it is in use.

Rate structure: at any given time t, the interest rate offered by bonds depends on two factors:

For a given level of reliability of issuers, the curve of rate as a function of maturity is called the rate structure (in French "courbe de rendement"). Here is the example of US government bonds in 2002:

Pricing of a second hand bond: we already said that the price of a second hand bond does not have to be and usually is not its face value. It all depends on the rate structure at the time of change of hands of the second hand bond. In short, if at the time of change of hands of our original 7 year 5% bond with 5 years to go (i.e. two years after its issue) the going rate for new 5 year bonds, of the same class of risk, is say 4%, then this 4% is the opportunity cost of capital of the second hand bond. Therefore we can compute, discounting the remaining future cash flows, its price today. Not surprisingly we shall find a price higher than the original face value:

The going price of the second hand bond with 5 years to go, and "competing" with new 5 year 4% bonds, is 1044 euros. Similarly, if the going rate is 3,56%, then, as we saw, the price of the second hand bond is 1065€. These are just plays around the above general discounting formula.

Impact of rate and maturity on the price of a second hand bond. You should remember from your first year course in finance, the important relationship between the price, the rate and the maturity of a second hand bond. It is summarized in the following formula: When rates decrease, the value of second hand bonds increase.

Here is an illustration. We start with three bonds, all of them with initial rate 5%, and initial value 100 euros. The first one has maturity 1 year (grey line), the second one has maturity 5 years (dotted line), and the third one has maturity 10 year (black line). We look at the impact of a change in interest rate (abscissa), immediately after issue, on the price (ordinate):

When rates decrease, the value of second hand bonds increase. And the effect is stronger on longer term bonds.

Read Levinson to learn more on the following topics: Rating agencies Interpreting the price of a bond Exchange rates and bond prices and returns Interpretation of the yield curve Spreads Enhancing security Repos Junk bonds International markets:

Bond indexes

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||